The Top Finds in Granby

Below are a ranking of our most important finds.

The Top Finds in Granby

Below are a ranking of our most important finds.

The following links take you to the artifact pictures for each pit/level that produced the artifact:

Number 1: Friday's Ferry

Site Found

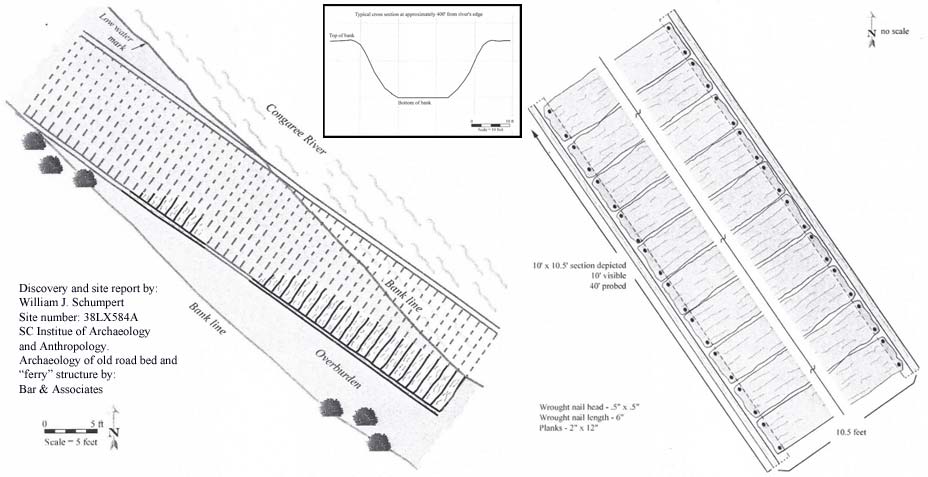

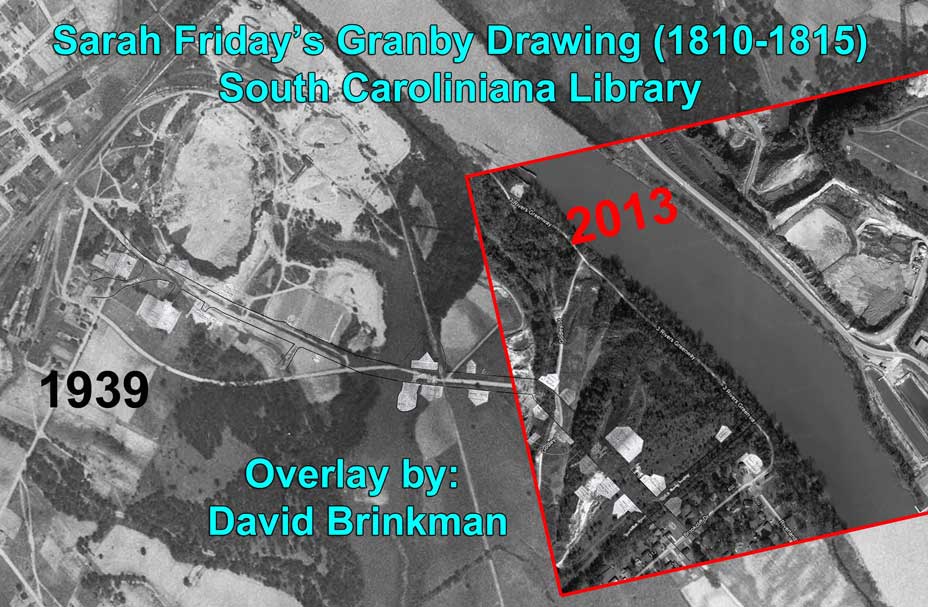

In 2007, as part of his project: Congaree River Historic Mapping

Project, land surveyor William J. Schumpert decided to checkout a

location on the Congaree River where his research pointed to the

possible location of one of South Carolina's most famous crossings.

Friday's

Ferry started in 1750 to help European settlers and friendly Native

Americans cross the river to Fort Congaree II. The town of Granby soon

formed around the ferry landing. The British operated Fort Granby

during the Revolution where sieges of the fort are recognized as the

most significant Revolutionary War events of Lexington and Richland

Counties. In 1786, Granby's "Friday's Ferry" was considered as the

location for the new Capital of South Carolina but was rejected because

of flooding and "health" issues. The new city of Columbia (and

Capital), formed across the river and President George Washington

crossed at Friday's Ferry in 1791 on his way to the smaller town of

Columbia. Granby's Wade Hampton would invest heavily in Columbia and he

built three bridges at Friday's Ferry in the 1790s.

As Schumpert paddled around where he thought the ferry

landing may have been, he noticed a mostly buried wooden structure in

the west bank of the Congaree River. Schumpert filed a site report with

the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology. A team of

archaeologists soon arrived and, not only verified the structure was

Granby period, but also found the old road bed leading to the location.

.

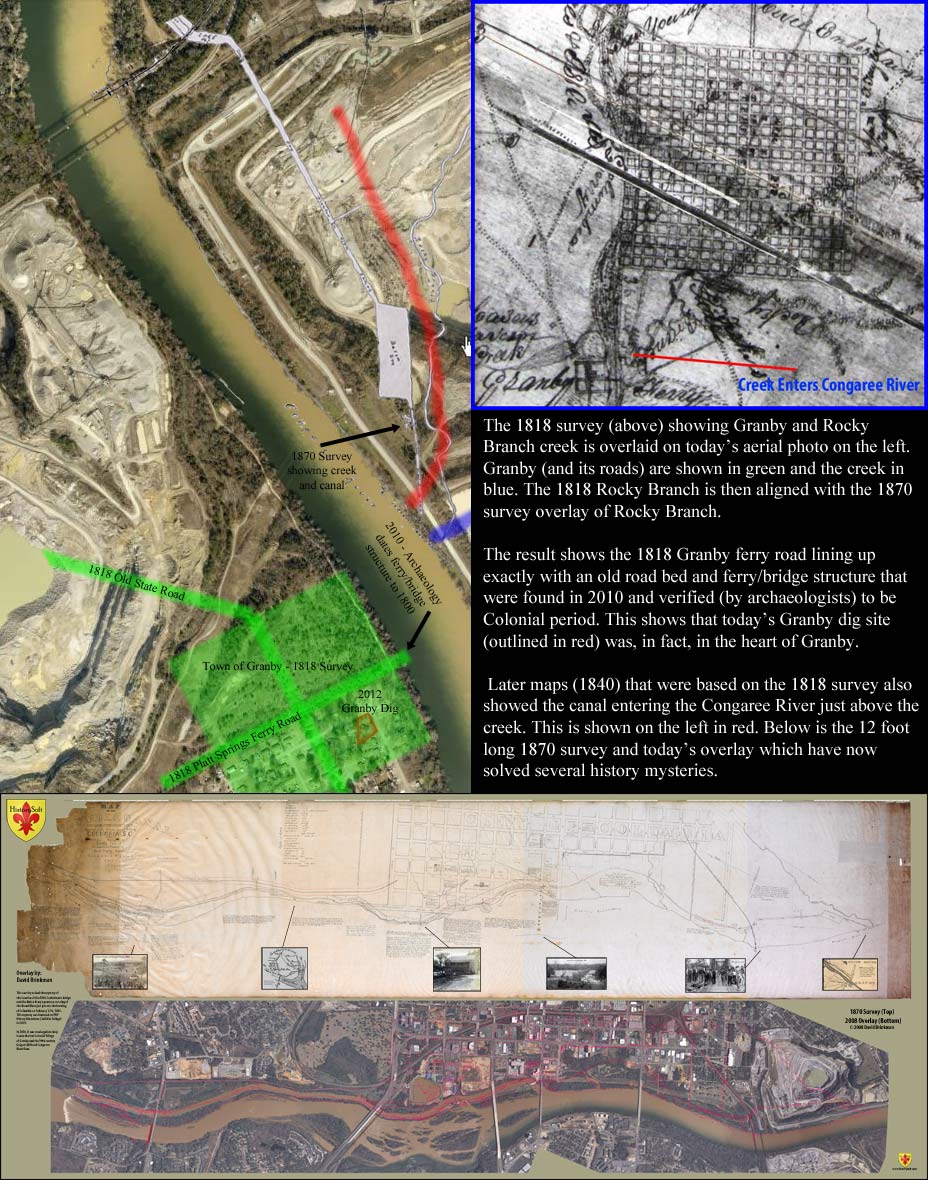

As word of the discovery slowly moved through the local history

community, David Brinkman began doing his own surveying in 2010 with

computer overlays of the State surveys of 1818 and the Columbia Canal

survey of 1870. The overlays agreed with Schumpert's work and Brinkman

now had an idea of where the boundaries of Granby fell on today's

landscape.

Just a few hundred feet from the discovered Ferry landing location,

Brinkman and his wife noticed a foreclosed house and were compelled, by

unknown forces, to purchase the neglected property. As major repairs

were made to the house, Brinkman did more Granby research and the idea

of archaeology on the site became enticing. Unable to acquire

professional help with the archaeology, the couple began their own

training and volunteered in a professional dig. In 2012, the Brinkmans

were ready to dig and, with other history friends, broke ground. They

quickly discovered Colonial period artifacts.

In September of 2013, the Granby dig team completed a

reconnaissance of the river around Friday's Ferry landing. A second

similar wooden structure was found downstream. This leads us to believe

that the structures may have been parts of the wooden Wade Hampton

bridges which were all destroyed or washed away by floods. Hampton

built all of his bridges at the site of Friday's Ferry. In 1798,

Hampton's last bridge was described as the largest building in South

Carolina. It was fully covered and stood 40 feet above the normal level

of the river. It was a popular place for parties and weddings.You can learn more about the Friday Ferry

site finds here.

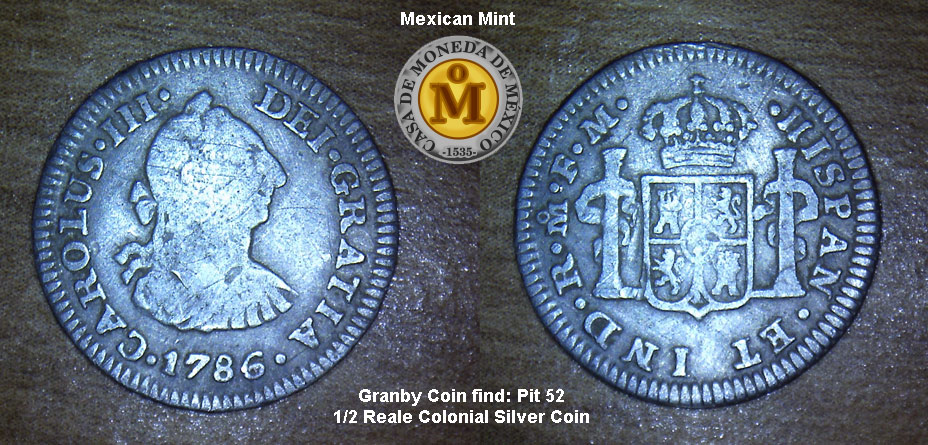

Number 2: Pit 52 - 1786

Silver coin

Coins are great because they give us a date for an item. In

this

case, the date was the year that it was decided not to move the Capital

of South Carolina to Granby but to a location two miles north on the

other side of the river. And so, Columbia was formed. For the next five

years, Granby would thrive and remained a larger and more popular

location. Floods and health issues in Granby in the 1790's, and the

continued growth of Columbia, would eventual be the death of Granby.

This coin, no doubt, was passed around in Granby during her most

prosperous years. This makes this, our number one dig artifact. You can learn more about the coin at this

link.

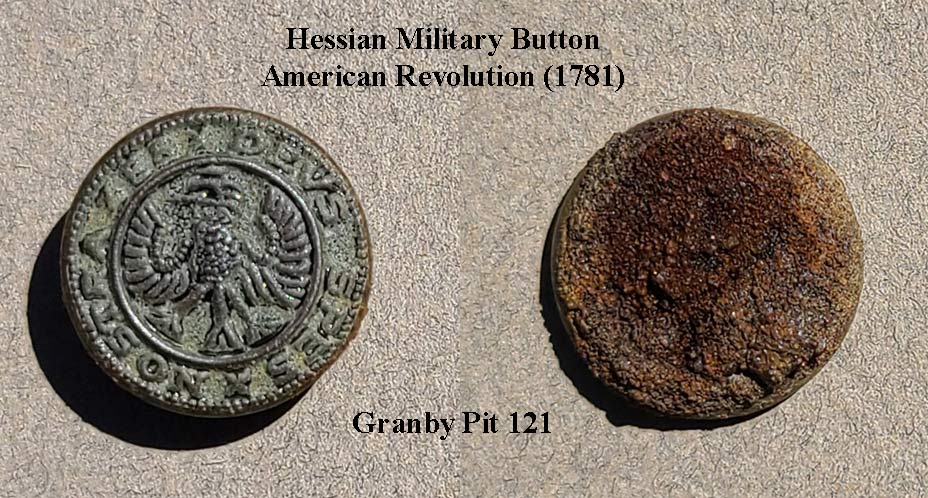

Number 3: Pit 121 - Hessian Military Button - Fort Granby.

In our continuation of a trench of pits to intersect what may be a row of burned slave quarters, we found a Hessian uniform button. The button has a three-legged Eagle and the Latin words: ES DEVS SPES NOSTRA, which translates to "God Is Our Hope."

Measurements

and comparisons to early 20th century reproductions proved that it was the real thing and would have been worn by a Hessian soldier between 1776 and 1781.

This is a top Granby find because it is the first dateable Revolutionary war item that we have found. Our many musket balls finds do not count because they can not be dated.

During the American Revolution, the British hired 30,000 German troops to help in their effort to defeat the Patriots.

These German fighters were known as Hessians.

From mountvernon.org: "Life in the Hessian Army was harsh. The system aimed to instill iron discipline, and the punishments could be brutal.

Still, morale was generally high. Officers were well-educated, promotion was by merit, and soldiers took pride in serving their prince and their people.

Furthermore, military service provided economic benefits. The families of soldiers were exempt from certain taxes, wages were higher than in farm work,

and there was the promise of booty (money earned through the sale of captured military property)

and plunder (property taken from civilians). "

There was a minimum height requirement to be a Hessian soldier. The uniform they wore made them look even larger. This was all done to intimidate the enemy.

The Hessians were greatly feared in America. The Hessians themselves were surprised by this. They

were shocked to learn that their enemy (Patriots) would often torture their prisoners, something the Hessians would never do.

From the records of the Revolution, we know that the British had at least 60 Hessians at Fort Granby. Some of these men may have been killed by the Patriots in an attack on

Friday's Ferry, just a few hundred feet from our Granby Dig site. This button could have been lost then, or maybe it was dropped when the British surrendered after the second siege of Fort Granby. Another possibility is that the uniforms of the captured Hessians were eventually given to slaves, and our button may have been

left here when a fire burned the slave quarters.

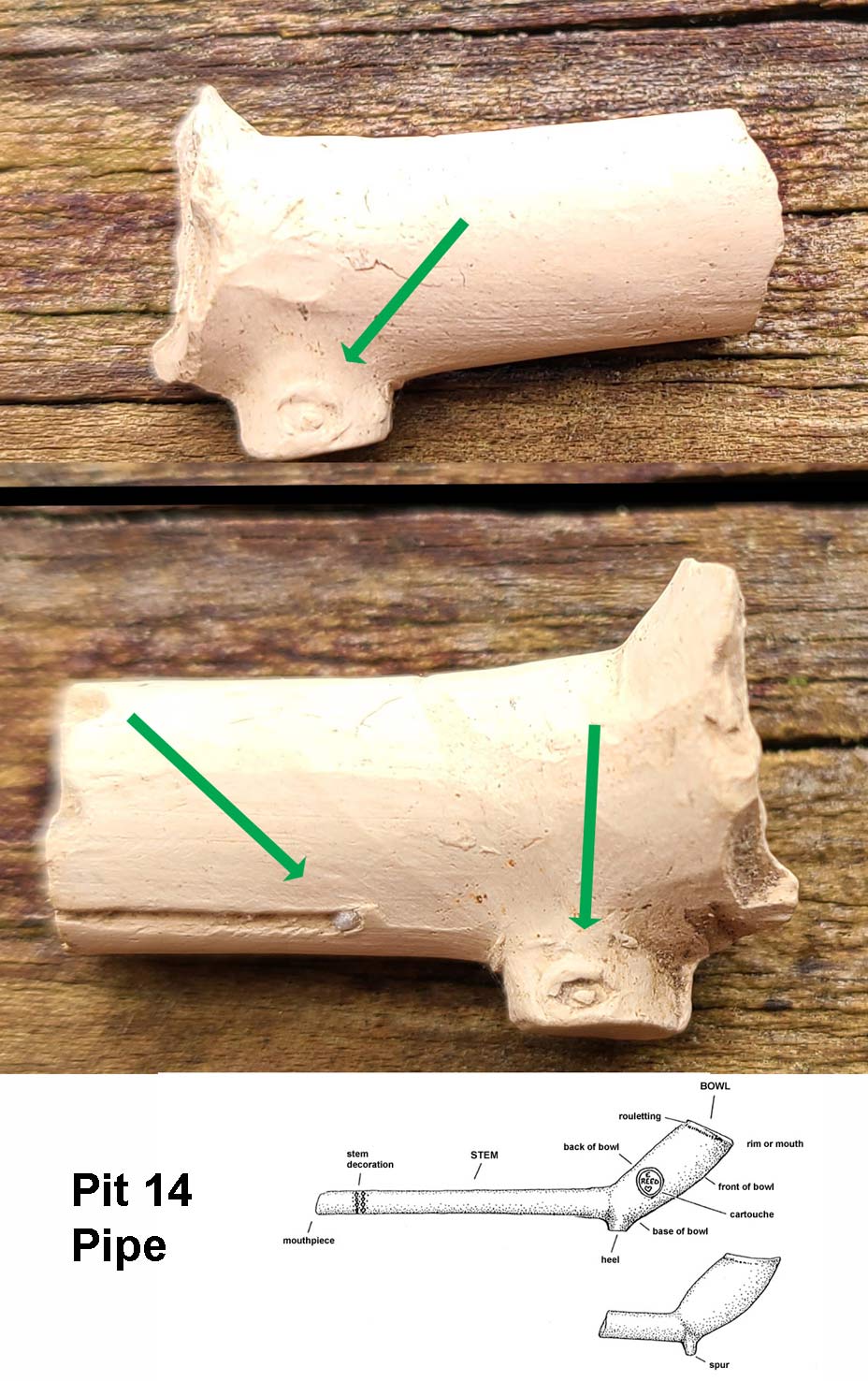

Number 4: Pit 85 - Pipe

bowl from Gouda, Holland.

This item is our largest pipe piece and four unique maker

marks

allow us to date it to the time 1740-1750. This is very important

because it gives proof to the theory that Thomas Brown may have lived

at this location. Brown died in 1747 and his land would be bought by

Martin Friday. Friday started a ferry at the northern border of the old

Brown property and this is what led to the development of Granby. Other

items found at the Granby site are also probably from Brown like two

early 18th century Jews harps (his main trade item with the Native

Americans), stoneware pottery, and 80% of our pipe stems are from the

period 1720-1750. It is amazing to think that this item was held by the

man who started what would become Granby. You

can learn more about the pipe pieces found in Granby at this link.

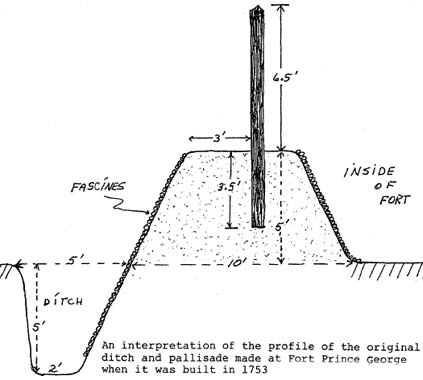

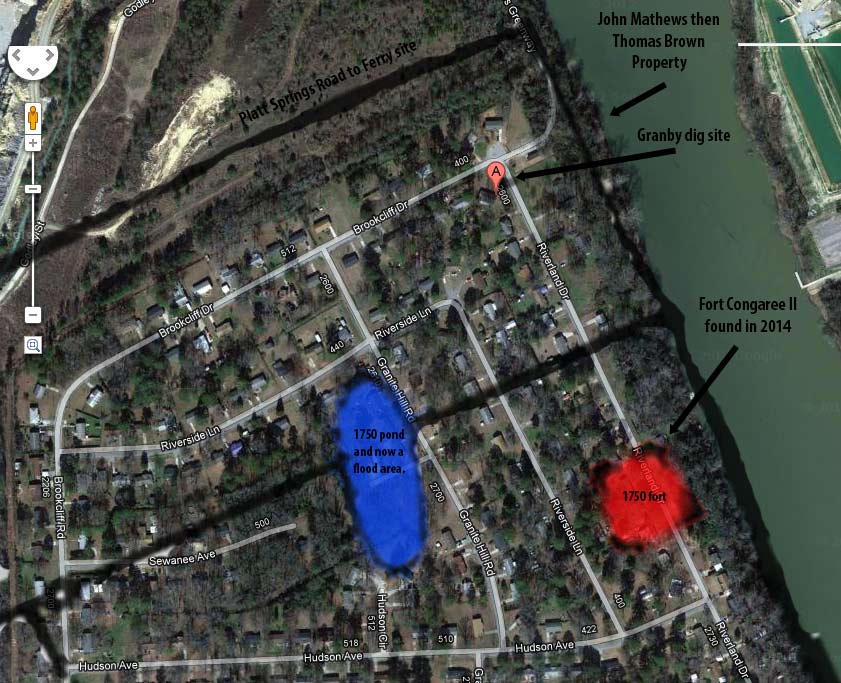

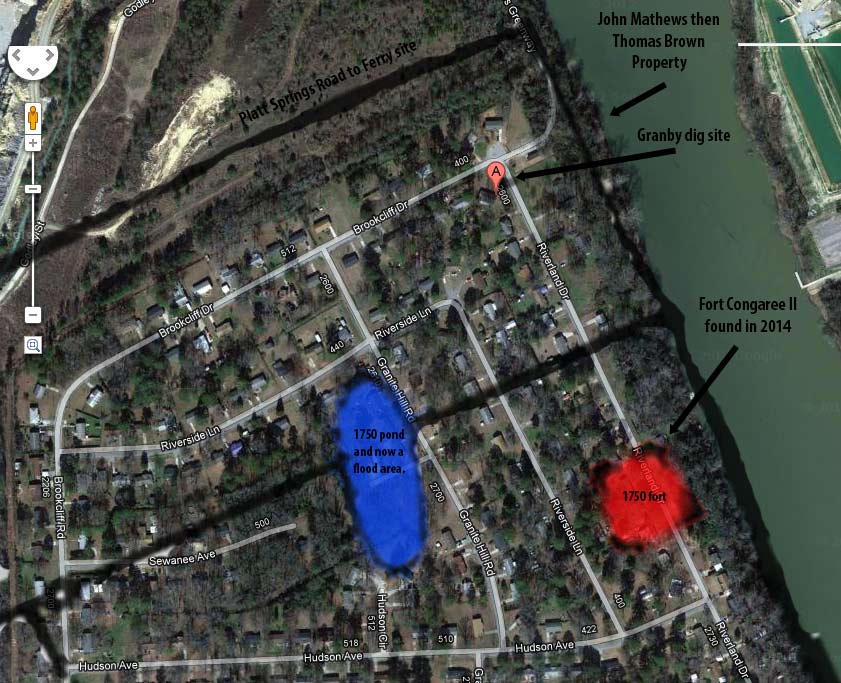

Number 5: Fort

Congaree II

Some people would vote this as the biggest find of the

Finding

Granby project. After Thomas Brown died in 1747, certain Native

Americans carried out a series of violent attacks and kidnapings

against the European settlers. During this time, Martin Friday acquired

Brown's property and started Friday's Ferry. A few hundred feet south

of this (at a location reserved for a fort in the original Saxe Gotha

survey from the 1730's), Fort Congaree II was completed in 1748. During

our Granby research, Colonial plats of the Granby area were studied.

One of them showed Fort Congaree II with a unique land feature that we

noticed was still present. Overlays were completed and we identified

the ideal place to do archaeology about 1000 feet south of the Granby

dig site.

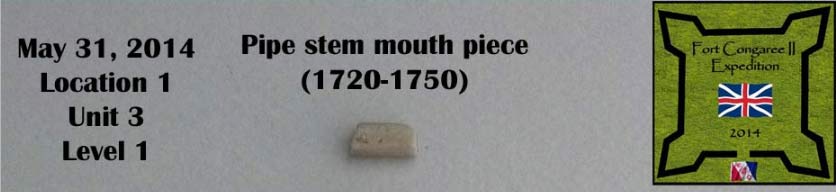

The Fort Congaree II Dig team completed a dozen dig days over the

summer of 2014 with the help of over 40 volunteers. All work was

overseen by Dr. Jon Leader (the South Carolina State Archaeologist) and

the team included 6 other archaeologists and many members of the Granby

dig team. The first dig location (14 units) was completed at the end of

August. When we started on May 31, 2014, within a couple of hours, the

team came across a feature in Unit 3 that had characteristics of a

palisade wall. Subsequent Units were opened to follow this feature. By

the end of August 2014, we had also found characteristics of a fill

area (the documented ditch around the outside of the fort) on both

sides of the possible wall feature. Our site selection was chosen to

hit the North-East bastion of the fort. The potential wall and ditch

finds would indicate this bastion. Most features were found at the

bottom of level 1 (10cm) or within level 2 (10-20cm). For this reason,

some pits were not dug beyond a 10-20cm depth. Some units were dug to a

depth of 40-50cm at which point artifacts were no longer found. We

found about 160 possible period artifacts in the 14 units. There were

several obvious period pottery pieces and several pipe pieces including

a 1720-1750 pipe stem. A .35 caliber musket ball was also found deep in

one of the units. On both sides of the possible wall feature, we found

period handmade nails.

You can learn more

about Fort Congaree II at this link.

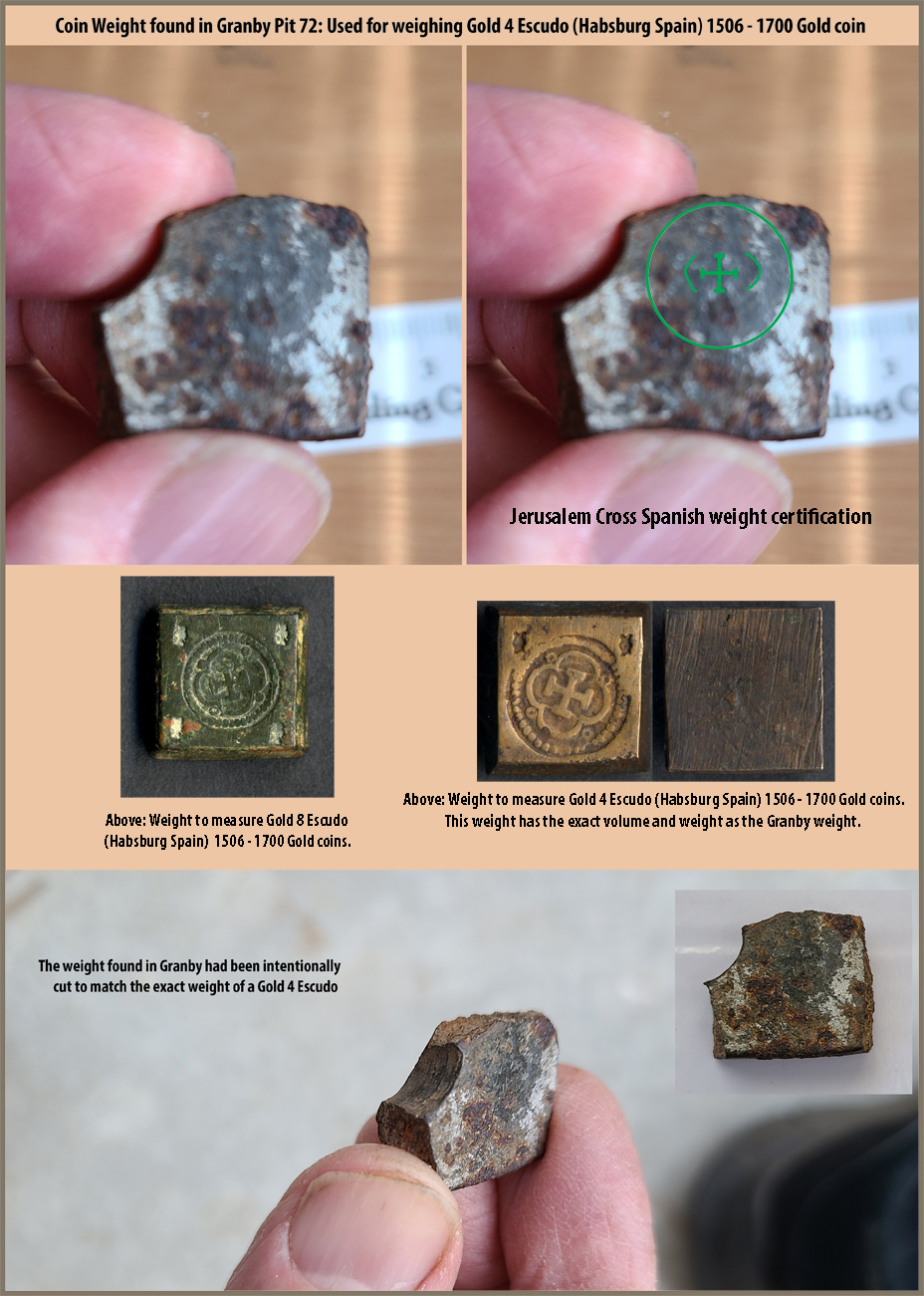

Number 6: Pit 72 - Coin Weight

First thought to be a modern-day machine-cut piece of steal, six years later we noticed a faint stamped image on the surface. A little research work would bring on the possibility that this was a Colonial period coin weight. Back in the day, dishonest people would shave or clip the gold or silver off of coins. This led to the need to weigh coins using known (certified) weights. On Halloween of 2014, in Granby pit 72, we found what I thought might be one of these weights but it had no clear markings on it as you would find in the 18th-century weights. I decided to pull that Granby artifact out again and take a closer look. With some nice sunlight coming through the window, I spotted the fading image of a Jerusalem Cross stamp. Measuring the volume of our artifact, and its weight, I found it exactly matched with the weights for a Spanish Gold 4 Escudo coin. These were made between 1520 and 1750. That's too early for Granby. What about the early Indian traders (1680-1720)? Why would they need to measure the weight of a Spanish Gold 4 Escudo coin? Could it be that the gold-seeking party of Hernando de Soto crossed here in 1540 and dropped this Spanish artifact?

After

consultation with the Florida Bureau of Archaeological Research, it

seems this coin weight most likely belonged to trader Thomas Brown and

was probably discarded after his death (in 1747) and the closing of his

trading post at our dig site. Escudo 4 weights and coins have been

found in the 1715 and 1733 fleet shipwrecks off of Florida. Given the

number of them found in wrecks, many Escudo 4s were probably making

their way into the SC backcountry during Brown's time here (1725 to

1747). Production of these stopped about 1750, shortly after Brown's

death so it is unlikely they were used during the Granby period

(1760-1830.) This find provides more proof that out site is where Brown

had his popular trading post.

Number 7: Pit 80 - Dalton point (arrowhead)

This Dalton point item is really special because of its age.

It

could be 10,000 years old! The Granby dig site is within the area of

the proposed 12,000 year history park where items of this age have been

found. In the Granby dig, we have found that the Granby and Thomas

Brown era items don't go much deeper than 50cms. In pit 80, we had just

leveled off at 50cms and a final shovel of dirt gave a "ching" and

there was one of our best finds. You

can learn more about the Indian Arrowheads found in Granby at this link.

Number 8: Archival

- Sarah Friday's Granby drawing (1810-1815)

Not all of our top finds are from digging dirt. Some come

from

digging the archives. In an old book about Columbia, I had found a

reference to this drawing made by a young Sarah Friday

(great-granddaughter of Martin Friday). The drawing eluded me for two

years until it was found in the South Carolinia Library. Although

Granby was on the downfall by 1810, Sarah does get a great snapshot of

the residents including what we believe were the owners of the site we

are digging: Samuel Johnston and family lived in Granby from 1790 until

about 1815. Sarah would marry John Bryce who would become a mayor of

Columbia. Her drawing may be the only surviving image of Granby. You can learn more about Sarah

Friday's drawing at this link.

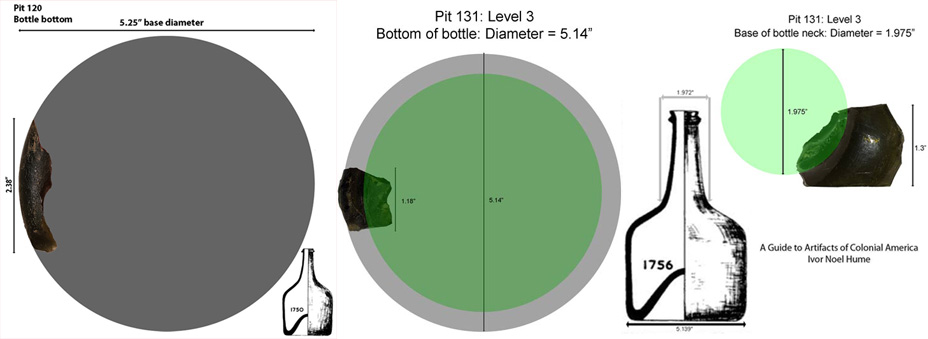

Number 9: Pits 120 and 131 - Bottle bottoms 1750-1756 - Fort Congaree II.

Pits 120 and 131 gave us fragments from the bottom of a green wine/beer bottle. These small pieces included a well defined curvature line that allowed us to determine the diameter of the bottle. Both bottles were a little larger than five inches. Of all the recorded bottles of Colonial Williamsburg, only the bottles from 1750 to 1756 had a bottom that was this large. This date range is very important because it is post Thomas Brown and pre-Granby, which means it must be related to Fort Congaree II. Remember that it was the Granby dig team that found Fort Congaree II in 2014, just 1000 feet south of the Granby dig site. So, just what was happening here between 1750 and 1756?

Fort Congaree II was built in 1748 and was in full operation by 1750.

From Dr. Dan Tortora's research and paper on Fort Congaree II:

In 1752, Robert Steill, a storekeeper on the main road from the northern colonies across the Congaree River from Saxe Gotha started a ferry service "to the Landing near the Congaree Fort."

In May 1754 Governor Glen granted Martin Friday a license and a monopoly on the public ferry. By 1754, a new road opened from Augusta to Saxe Gotha Town, and the Fort featured prominently in the increased river traffic and settlement to the town.

On July 3, 1754, Nine hundred French soldiers surrounded the three hundred Virginian militiamen and South Carolina Independents at Fort Necessity. Fort Congaree II Commander Peter Mercier and six of his men came to help the young George Washington at Fort Necessity. They gave their lives saving Washington.

Life at the fort resembled life in other garrisons throughout the British Empire. A drummer was stationed at the fort until the Commons House paid and discharged him on April 2, 1756.

The Decline of Fort Congaree II: In 1758 and 1759 Cherokee warriors and European settlers clashed on the southern frontiers. Diplomacy failed, and South Carolina declared war on the Cherokee Indians. The Congarees (the Fort area) hosted British and Provincial soldiers on three separate military expeditions against the Cherokee. Governor Lyttelton visited the Congarees with 1,100 Provincials in 1759.

In 1761, Colonel James Grant led 2,900 British Regulars and South Carolina Provincials, including Francis Marion, John and William Moultrie, Isaac Huger, and Andrew Pickens - against the Cherokee Indians. These men trained and camped at and around the area of Fort Congaree II.

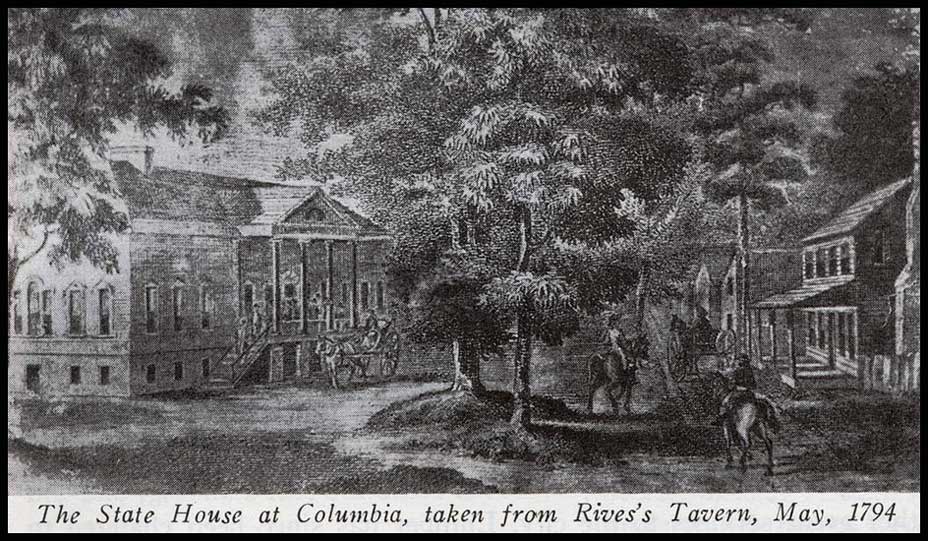

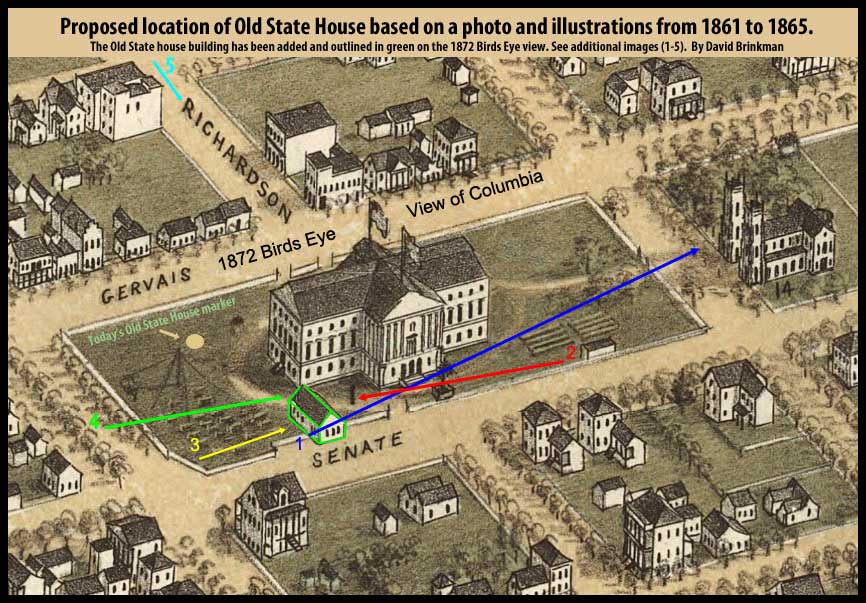

Number 10: The Old

State House and Rives Tavern

Another project spawned by our Granby research.. Timothy

Rives was

the first Granby tavern owner just after the Revolutionary war. Rives

moved his operation to the new Capital city of Columbia in 1790 at the

south-west corner of Richardson (Main) and Senate Streets, just across

the street from the Old State House. The above 1794 illustration shows

the Tavern and Old State House. Research began to locate the tavern and

it seemed the best shot at doing that was to search for the basement

foundations of the Old State House which was also burned in 1865. Many

measurements were taken from drawings of the old State House and of a

floor plan from the 1830s. The floor plan had no dimensions but I was

able to interpolate the size based on carefully drawn steps from the

basement to the first floor. The result was a building that was 80' X

37.5'. I verified these outer dimensions by measuring the size of the

Palmetto (Mexican War) monument on today's State House grounds. That

monument stood in front of the Old State House between 1855 and 1861. A

detailed illustration was made of the building and monument in 1861.

The relative sizes matched with the interpolated 80'X35.5' size of the

building. Continuing the math, the basement landing would have been 2'

to 3' below ground. After determining the exact size and location of

the old State House, the site was visited after the great flood of

October of 2015. A number of artifacts were observed in an eroded area

where the corner of the Old State would have stood. A number of these

artifacts matched the types and age of our Granby building artifacts.

That Granby building happened to be the same age of the Old State House

(built between 1788 and 1790). One common item was imported English

window glass. Multiple pieces of this melted glass were found and one

appeared to have lead in its center (lead strips were used in that

period to hold pieces of window glass together). Unlike glass of today,

this old glass (and lead) will melt at the temperature that wood burns

so it would be expected that this melted glass would be found in the

ruins of the Old State House. Additional measurements were made using

period documentation and maps to determine the relative position of

Rives Tavern to the Old State House. Rives tavern was sold a couple of

times but remained a tavern until the building was burned by the Union

Army in 1865. Inspecting this other location led to the discovery (on

the ground surface) of late 18th century pottery and green wine glass

as well as ginger beer bottle fragments from 1830 to 1865. They were,

obviously, artifacts of Rives Tavern. This research lays the groundwork

for archaeological work to excavate the Old State House and tavern as

well as finding what may be hidden in the ruins of the Old State House (See the

research paper I completed on the lost Charleston Calhoun statue at

this link).

Number 11: Found in most

pits: - Pearlware Kitchen Pottery

Kitchen pottery is our most common artifact. Over 20% of our

artifacts are in this category. We have found many different types of

Kitchen pottery but, in general, most of these are imported from

England and are not something the average person would have afforded.

This is not surprising given documentation that indicates Granbians

were relatively wealthy people. As far as aging the pottery pieces, the

most easy type to identify is the Pearlware type. It is very common in

our finds as can be seen in the above picture from pit 22 where the

Pearlware stands-out with its unique bluish tint. Pearlware like this

was only made from 1775-1840 which covers the Granby period.

Number 12: Pit 51 and 67 -

Jews Harps

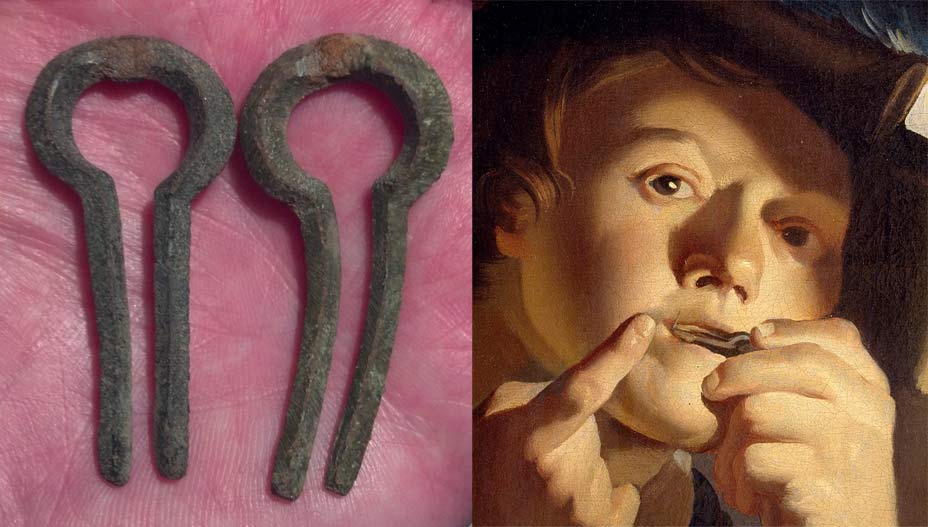

This musical item caught us by surprise in pit 51 but by the

time

we found a second one, in pit 67, we had learned that Indian Trader

Thomas Brown had been trading Jews Harps with the Natives. In fact, it

was the only item left in his inventory at his death in 1747. A Jews

harp was useless if the vibrating tongue was broken off. In pit 67, we

found the Jews harp mixed with charcoal and, at the same level, what

appeared to be Native American pottery. Brown's wife was a Catawba

Indian. Maybe he was playing his harp for his wife by the fire when the

instrument was broken and, thus, thrown into the fire. The charcoal

artifact excavated with the harp may tell us, through carbon dating,

the age of this event.You can learn

more about the Jews harp at this link.

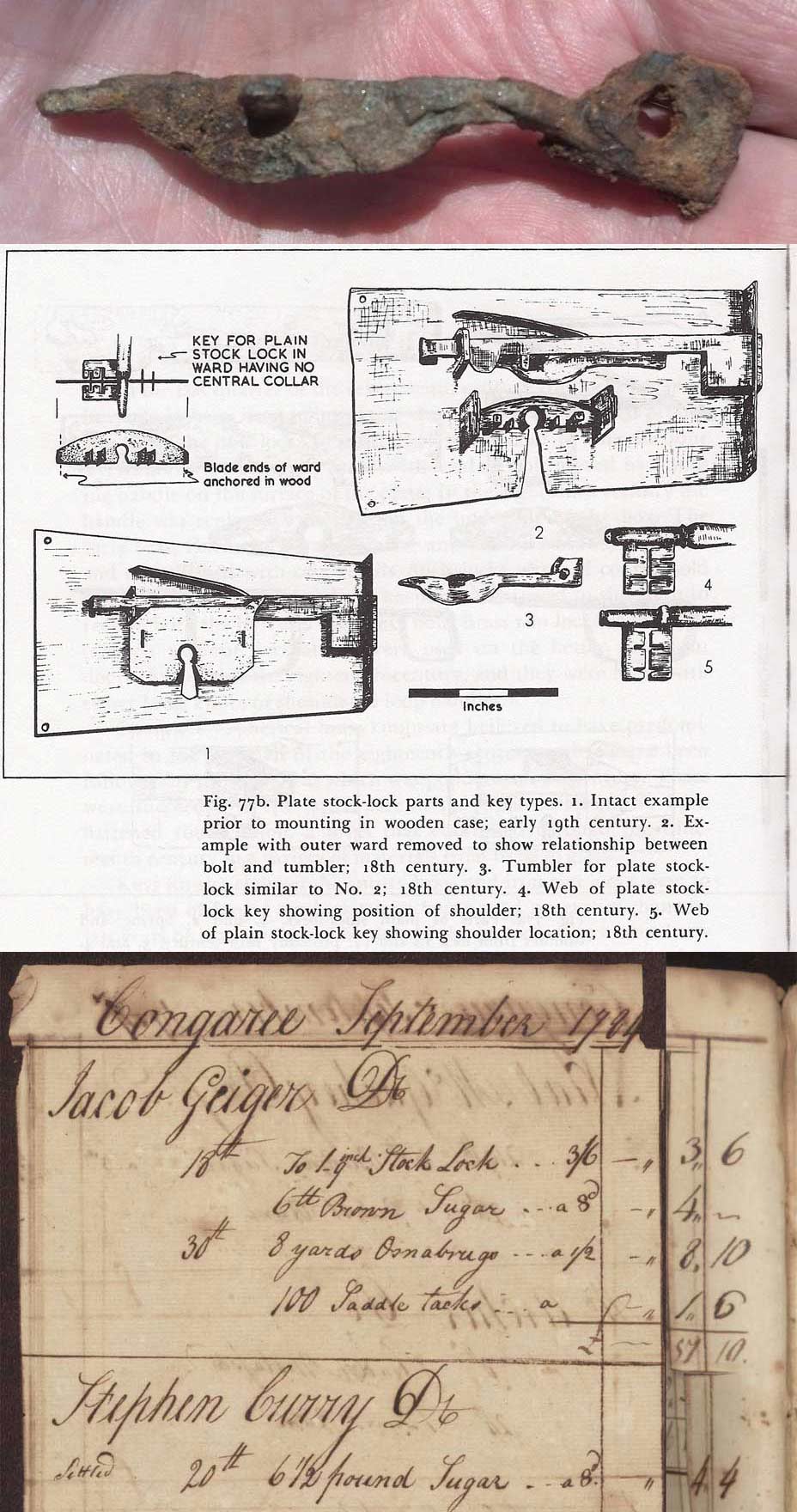

Number 13: Pit 37 - Stock

Lock tumbler

At first, we thought this was a rusty nail but cleaning showed it was something very unique. It was a mystery until I stumbled across it in a book about Colonial American artifacts. It was the lock tumbler in the standard English 9 inch stock lock. Probably the lock on the house's front door. Making this find even more fascinating is that fact that we found the same lock purchased by Jacob Geiger in 1784 as recorded in the Congarees Store account book (held by the Cayce Museum). You can learn more about the lock piece at this link.

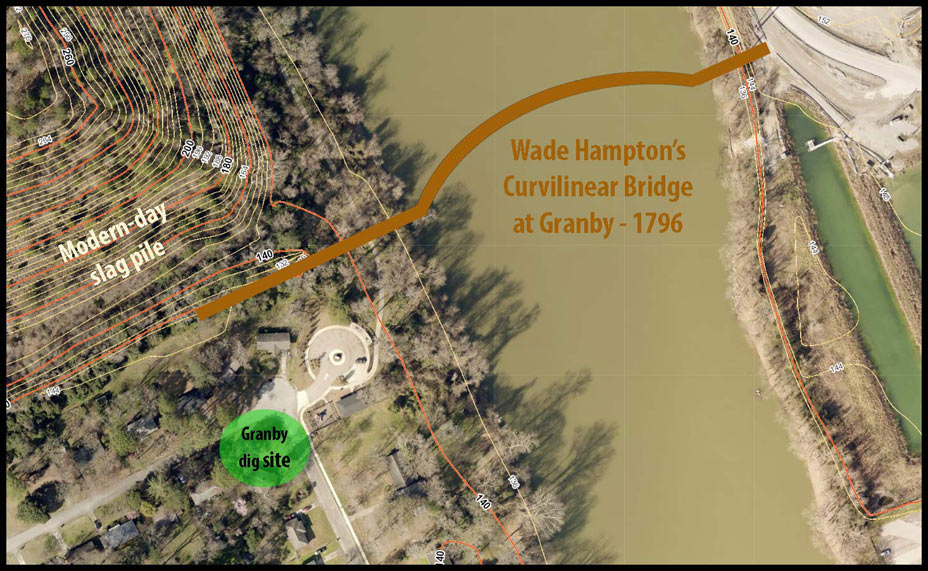

Number 14: River Dive Prep - Wade Hampton's 1796 Curvilinear Bridge

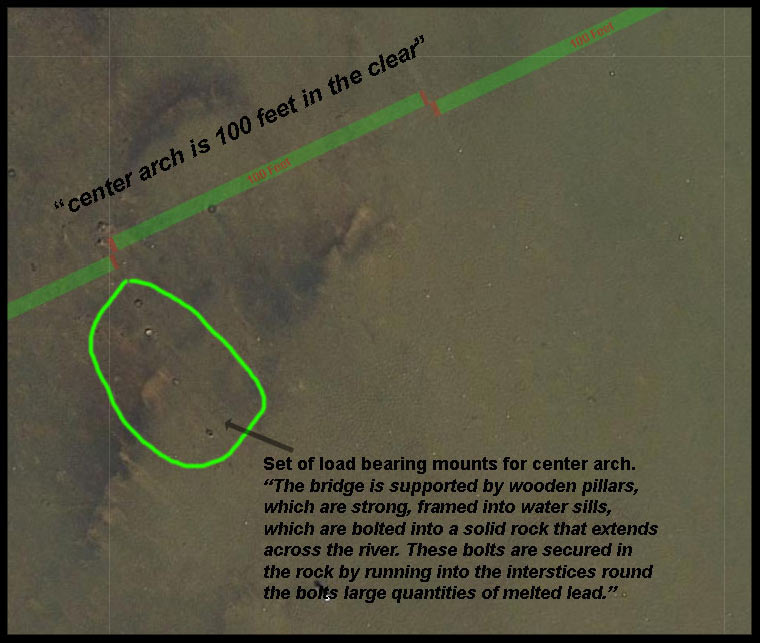

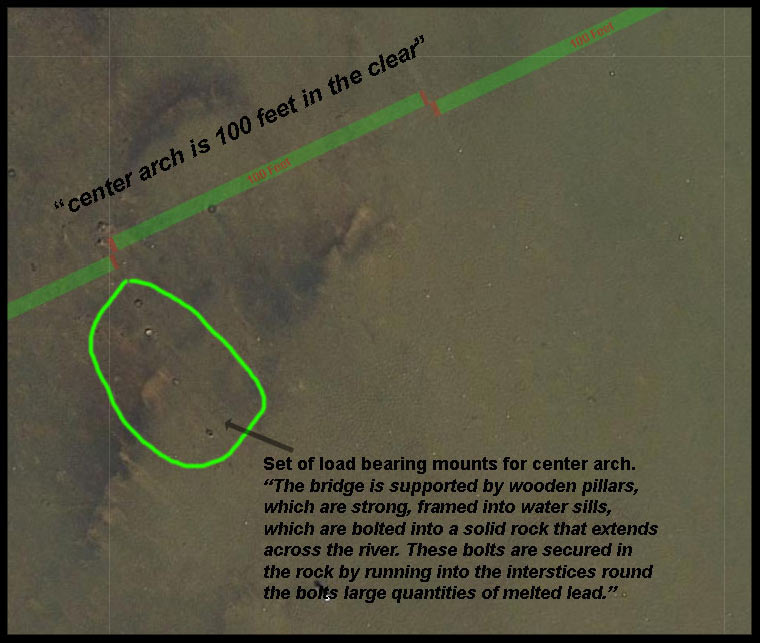

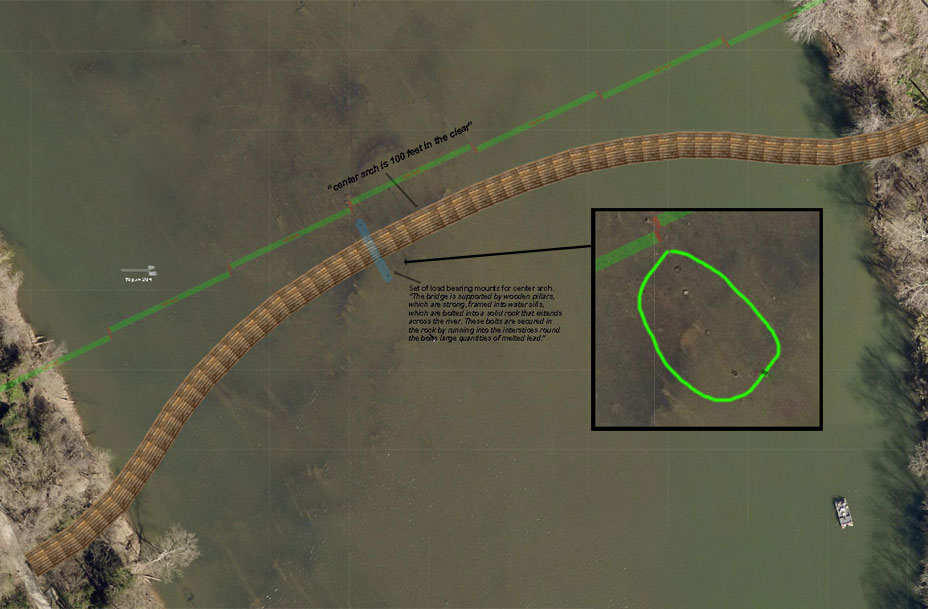

In 2017, we noticed an aerial photo of the Granby dig site showed the Congaree River at an unusually low level. Between where we had found centuries-old structures on the east and west banks, the photo showed something very unique in the middle of the river. Below are pictures from the west and east sides of the river showing the previously discovered structures in the river bank.

Looking a little upstream, the 2017 aerial photo revealed obvious man-made items just a couple of feet below the water's surface.

In 1796, at this location, Wade Hampton built the world's first curvilinear bridge. It was described as being horizontally arched up-river with a straight 100-foot vertical arch section in the center, which was open of piers so that wide boats could pass through. At each end of this center-section was a set of strong piers that were mounted into the river bed with lead. The 2017 aerial photo shows a line of mount points on the west side of where the 100-foot center section of the bridge would have been. The east side is in deeper water and probably covered with silt, although the tip of one point is visible, and it is exactly 100 feet perpendicular to the line of other mount points. Jedediah Morse's "The American Universal Geography" (1796, page 675), gives the following description of Hampton's final 1796 bridge:

"A bridge has lately been erected over the Congaree River, at a small town called Granby, about two miles below the confluence of

Saluda and Broad rivers. This bridge is remarkable for its being built in a curvilinear direction with the arch up-stream, which contributes much to its strength and also for its height, being 40 feet above the ordinary level of the water. The bridge is supported by wooden pillars, which are strong, framed into water sills, which are bolted into a solid rock that extends across the river. These bolts are secured in the rock by running into the interstices around the bolts large quantities of melted lead. The great height of the bridge was requisite to secure it from the freshets which rise here to a great degree, the current of which is so rapid as to carry before it everything which should present to its fury any considerable surface.

The center arch is upwards of 100 feet in the clear, to give a passage to large trees brought down by the flood in great abundance,

and would otherwise, by lodging against the bridge, prove fatal to it, as was the case with one, some years since, which had been erected in the same place. For this useful work, the country is indebted to an enterprising and valuable citizen, Colonel Wade Hampton,

who has a right of toll secured to him by the legislature for 100 years."

The bridge height of 40 feet above the water matches, exactly, the height of the bluff on the East side of the Congaree River. The slight bluff on the west side of the river, however, is not nearly as high. According to the South Carolina bridge specifications of 1820 (which had probably been universal standards for many years), the slope to a bridge can not be more than one foot per 30 feet. This would have required a significant ramp extension to the bridge on the west side of the river. Only the main portion of the bridge, over the river, would have been covered. The only reason for having Covered bridges was to protect the massive trusses and arches from nature's elements.

Modern-day historians have documented that the world's first curvilinear bridge was the Colorado Street Bridge (built-in 1912) in

Pasadena, California. Jedediah Morse's 1796 "The American Universal Geography" proves they were wrong by over 100 years.

Historians have also suggested that the Schuylkill Bridge, High Street, Philadelphia, completed in 1805, may have been the first documented covered bridge in the United States. This is very strange given that the Europeans had been building covered bridges for many centuries before this. In fact, a few European covered bridges still exist, which are over 400 years old, like the Schlossbrucke (1514) in Zwingen, Switzerland, and Spreuerbrucke (1568) in Luzern, Switzerland, are two examples.

Opened to traffic on January 1, 1805, the Schuylkill Permanent Bridge was heralded as an engineering masterpiece and "an honor to its inventor for its originality of architecture, and its excellence of mechanism." Due to the extraordinarily high cost of construction, the board of directors corresponded with Palmer about the possibility of covering the bridge to protect their investment from the weather. In his reply, Palmer affirmed the board's decision with this statement:

"I am an advocate for weatherboarding and roofing, although there are some that say I argue

much against my own interest. . . . It is sincerely my opinion that the Schuylkill bridge will last thirty and perhaps forty years, if well covered. . . . I think it would be sporting with property to suffer this beautiful piece of architecture . . . which has been built at such a great expense and danger, to fall into ruins in 10 or 12 years!"

The covered Schuylkill bridge, as predicted by Palmer, stood for forty-five years until it was replaced in 1850.

Wade Hampton was no ordinary man. His genius spanned many fields, including construction and commerce. Paying for the Congaree Bridge out of his own pocket, he would have used all the modern bridge building knowledge to make sure his bridge lasted as close to the 100 years he was given rights to hold and operate the bridge. Hampton would have had easy access to "Plan of a Bridge to be Built over Schuylkill," which was published in The Columbian Magazine in January 1787. It's no coincidence that our initial research of Hampton's bridge led us to a Burr arch with ten trusses in a 100-foot segment (for Hampton's portion of the bridge, which was in the center of the river.) We later found that the 1787 published Schuylkill covered bridge plan also had ten trusses in a 100-foot segment Burr Arch.

I decided to recreate the bridge using wood sections just like the one found on the east bank of the river (two 10 foot wide parallel sections that are 40 feet long. Following a curvilinear path toward those mount points, I straightened it out at the point of the newly discovered mounts over the next 100 feet. I then mirrored the east side of the bridge, and it made a perfect landing on the other side, completely symmetrical. This is what Wade Hampton's bridge looked like from the air. When you add a divider for two-way traffic and the outside walls of the covered bridge, it was probably five feet wider than this. In all, that means the covered structure was 20,000 square feet. A period description said it was the largest building in South Carolina in 1796. It stood forty feet above the normal level of the river. It hosted many weddings and parties. Below is the recreation of Hampton's bridge.

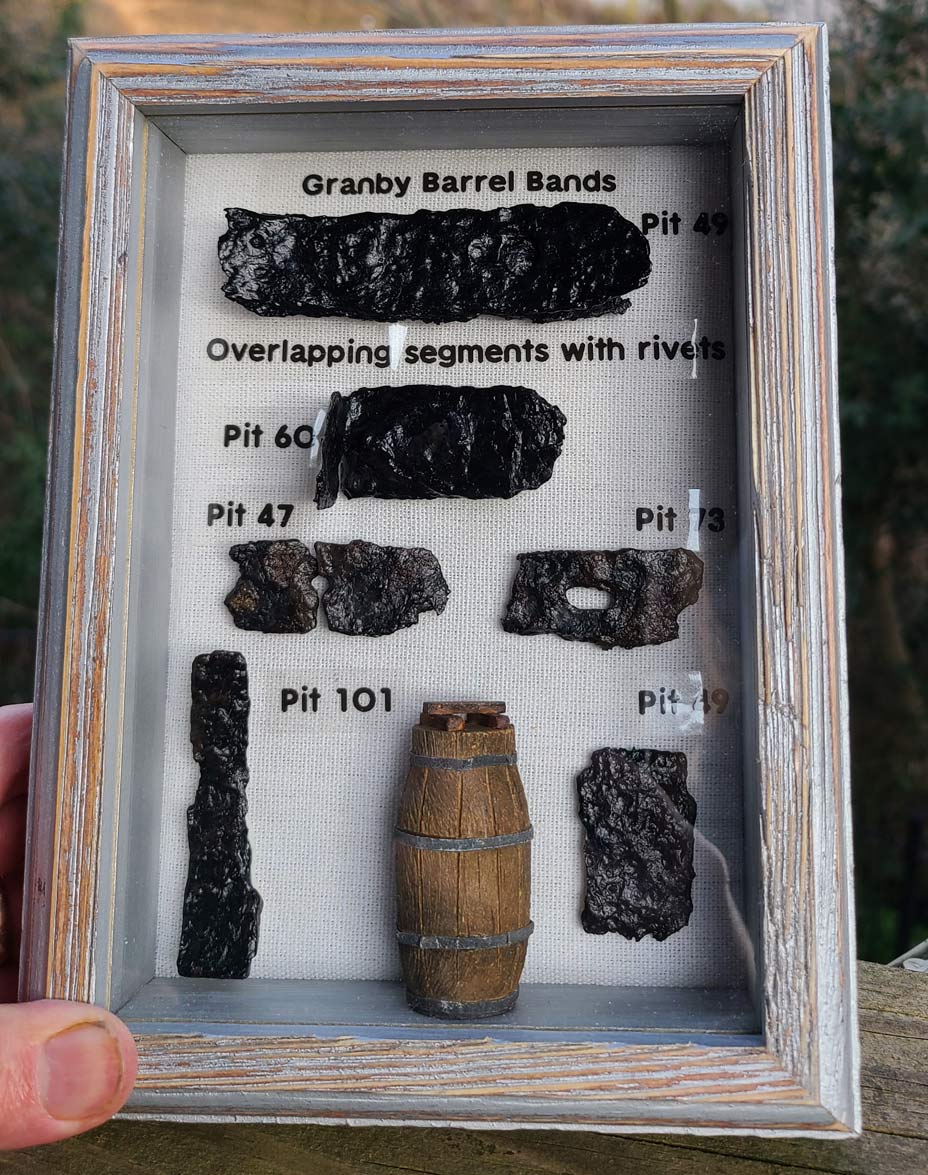

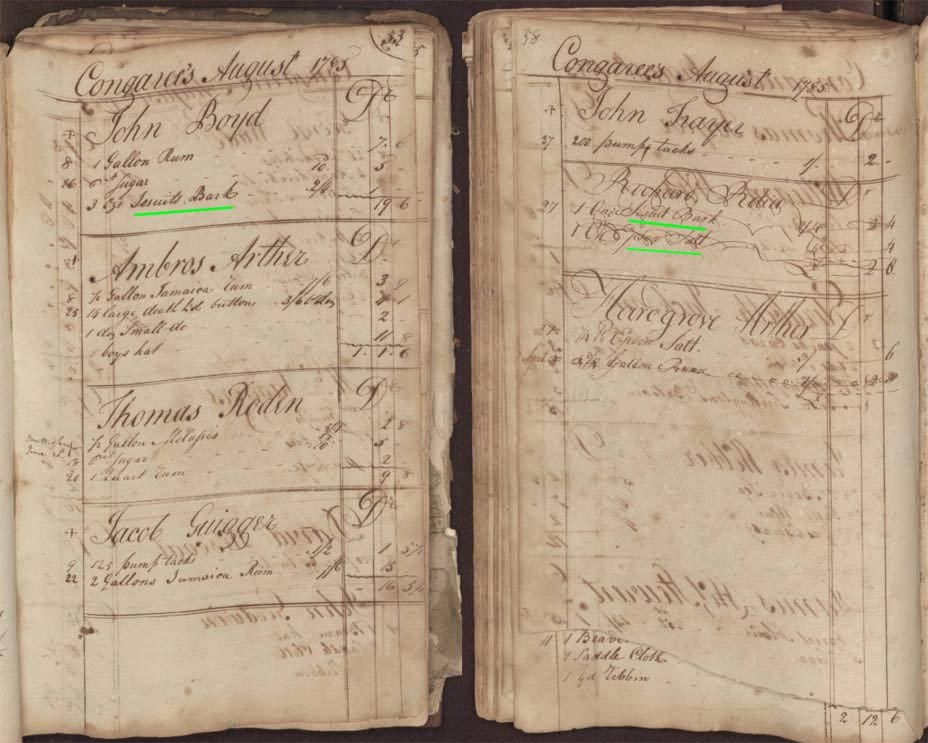

Number 15: Pit 49 and others - Barrels

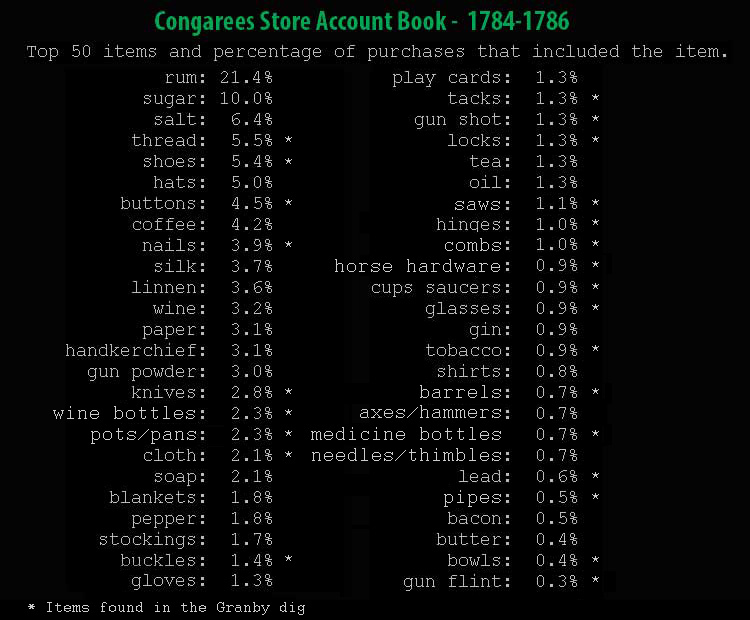

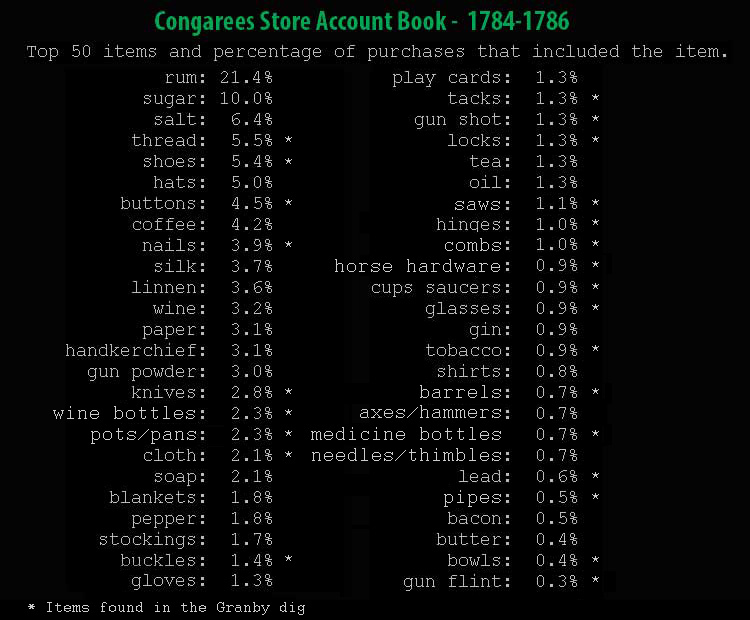

Above is a small display of a few of the many barrel band pieces we have found in the Granby dig. In the past, part of the fun in the Granby dig has been the after beer drinking. Unfortunately, there's not much evidence to support that the Granbians were big beer drinkers. The components to make a good beer may have been hard to come by during this time. The Congarees Store Account book (you can see this 1784-1786 book at the Cayce Historical Museum) shows that, by far, the most popular item purchased was rum. So, I had a custom 3L barrel made (see below) to provide our diggers with some Jamaica Rum (the most popular rum in Colonial Granby.) Samuel Johnston bought the Granby house (which we have been digging) back in 1790 and probably lived there until about 1820. Martin Friday had a mill in Granby in 1750 and his great-granddaughter Sarah Friday made a drawing of Granby in about 1810 which shows a mill next to "Friday's Entertainments" tavern and a distillery on the other side.

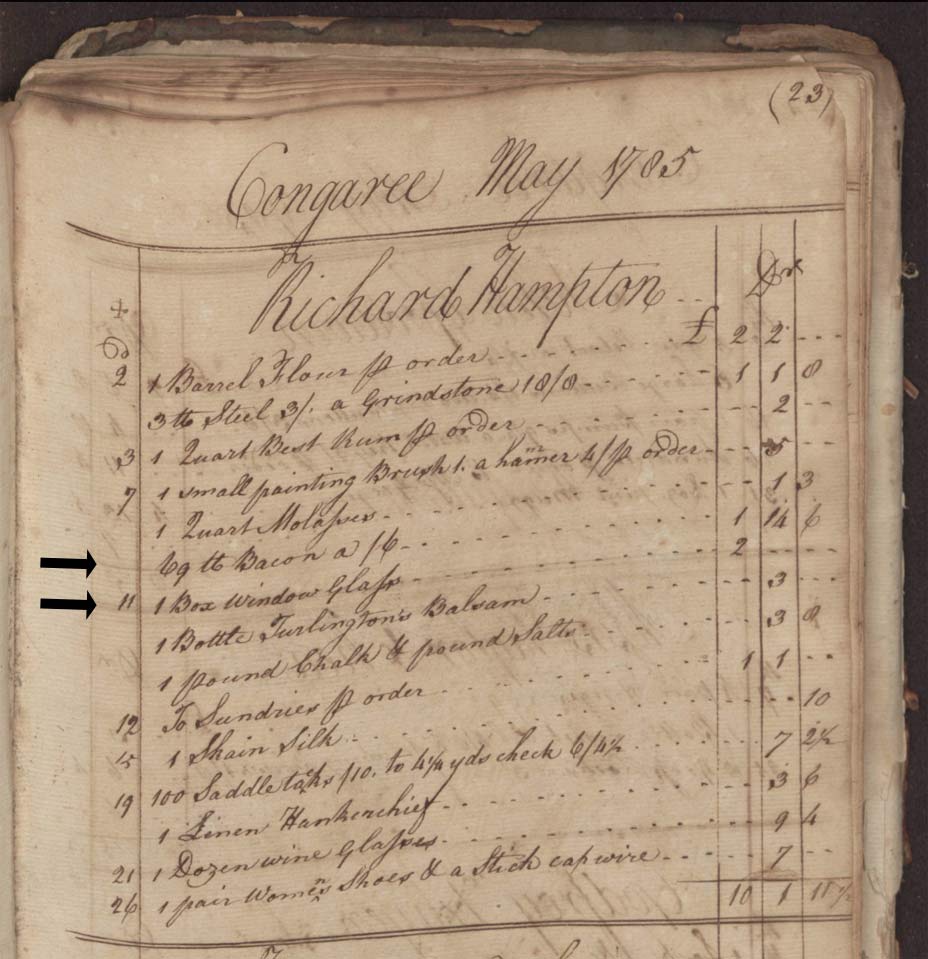

The basic and most popular barrel in demand was an airtight, fifty two gallon (200 liter) barrel made

of thirty-one to thirty-three staves with a lid at each end. The preferred wood was oak, for its density,

and was also desired for the good aging of spirits. Certain types of barrels were also made with pine, especially yellow pine. The following entry in the 1785 Congarees Store account book (for Richard Hampton) shows that barrels were for more than just spirits. Using the given sales prices, we were able to confirm that that barrel of

flour contained the standard 180-195 lbs of flour. The 69 lbs of pork/bacon would have been a half-barrel.

Tobacco required the largest barrel (hogshead). There were only two tobacco inspection stations in SC

during this period. They were Charlestown and Granby. According to Sarah Friday's drawing, the Granby inspection station (and a

huge tobacco warehouse) was across the road from our Samuel Johnston's house dig site. A metal detector scan of that area (no digging involved) revealed many iron artifacts are in the ground. The Granby nails are too small and too deep for most metal detectors but the larger barrel bands would be detectable.

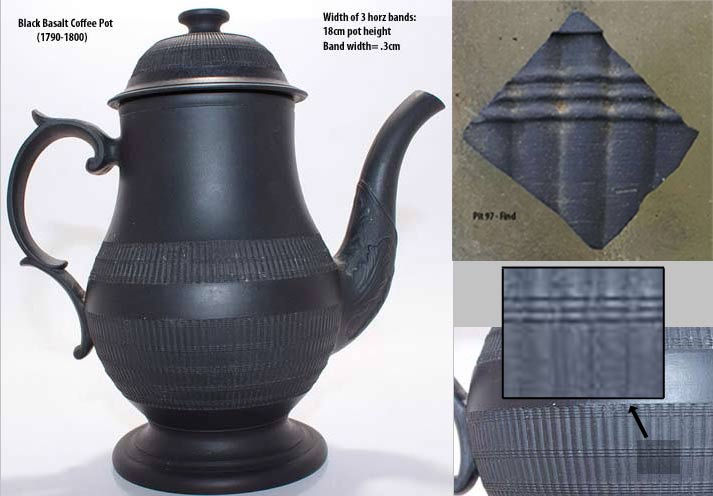

Number 16: Pit 97 - Black

Basalt (Wedgwood) Coffee/Tea Pot

Flooding and health problems in Granby, coupled with the

development of Columbia, led to an exodus of people in the 1790s. By

1815, Granby may have lost half of its residents. Many more would leave

after the county seat was moved from Granby to the new town of

Lexington in 1818. It is documented that only three families were in

Granby in 1850 and many of the old homes were colasping. General

William Sherman noted that part of his troops camped in "Old Granby"

just defore the invasion of Columbia in 1865. From that point on, half

of Granby became farmland and the other half fell victim to the Quarry

and quarry slag piles. Our dig site was farmland as can be seen in a

1939 aerial photo. Not surprising, the artifacts we find have been

broken into small pieces by the plow. Sometimes we can find a critical

part of a bottle which allows us to identify the item and its age.

Ceramic types and ages can be identified from a small piece but

determining what the whole item was (bowl, plate, cup) is much more

difficult. In Pit 97, however, we got lucky with a rare ceramic piece

that had a unique design on it. This Black Basalt (Wedgwood) piece was

almost certainly a specific coffee/tea pot that was made by Josiah

Wedgwood in England around 1790. A pot like this was very expensive and

goes along when documentation that suggests Granbians were wealthy

people. Period newspaper ads from Charles Town show the price for a

dinner-set of "Wedgwood and Liverpool" cost what today would be $2000

to $3200. You can learn more about

the coffee/tea pot piece at this link.

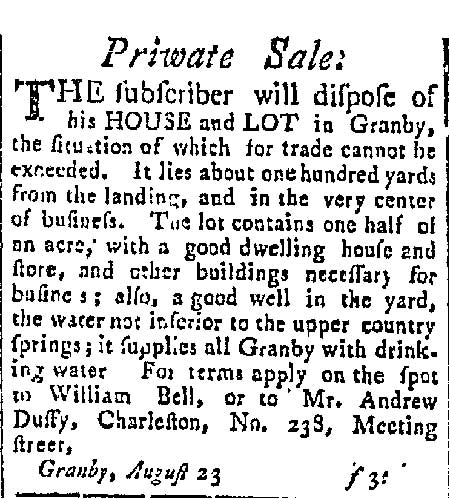

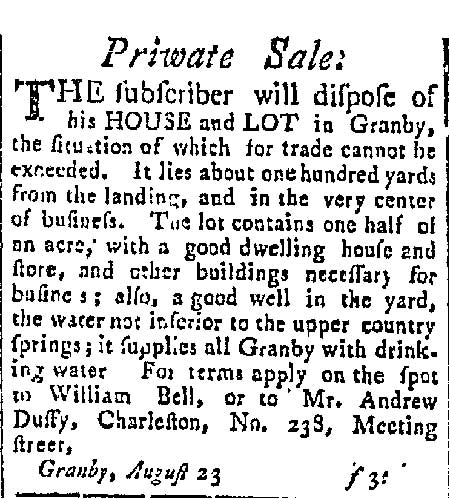

Number 17: Archival:

1790 Newspaper ad for our Granby property.

Another big find in the library. This 1790 ad describes a lot

that

was 100 yards from the Granby Ferry landing. This could be the property

of our dig site but it could also be several other properties. We know

a large tobacco warehouse and inspection station was at the ferry site

during this time so that would narrow this down to maybe only two

possible home sites. We believe, based on Sarah Friday's drawing of

Granby (1810-1815), that the Samuel Johnston family lived at our dig

site. This is shown in Sarah's drawing. Samuel married Catherine

Harrison in 1790 which seems to be the time that Samuel bought the

Granby house and property. We think there is a very good possibility

that Samuel (who did not live in the area before his marriage) found

out about the Granby property through this August 1790 ad in the City

Gazette of Charlestown, SC. You

can learn more about who lived in Granby at this link.

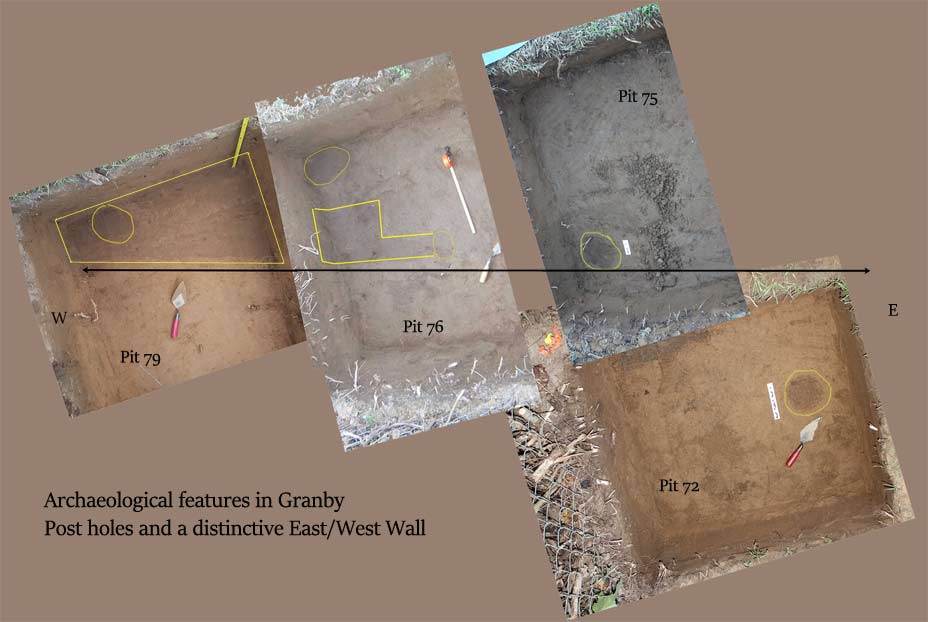

Number 18: Pit

72,75,76,and 79 - Aligned Post Holes and building features

Not all finds in Granby are archival or archaeological

artifacts.

Some finds are archaeological features. A simple way to describe these

features is as a stain in the ground. A wood post left in the ground

will leave an obvious dark round spot. Excavated and filled areas will

leave a color change. We believe the combination of these features is a

building structure. This find occurred over four adjacent pits. Based

on Granby artifacts found in this same area (brick, nails and window

glass) it would probably be the north-east corner of the Johnston house

(1790-1815). But, we have also found artifacts from two generations

before the Johnston House. Indian trader Thomas Brown lived here

(1730-1747) so it could be his cabin. It will take more digging to

solve this mystery. You can

learn more about these post holes at this link.

Number 19: Pit

114 - Preserved Wood Post

As we reached the normal maximum depth of 50cm, in pit 114, we were still finding a significant number of artifacts. Continuing the dig, we reached 60cm and found what would prove to be a huge surprise. A hard object that felt like wood appeared. Very close to it was one of the largest brick fragments we have found and also a square nail. This was all on the west side of the pit and not in the disturbed east side (gas line trench.) At this point, we began a careful excavation around the wood object. At first, we thought it might be a tree stump, but this is in an easement area where no trees have grown since this neighborhood was created in 1960. And before that, this land had been continuously plowed for over 100 years. The depth at which it was found was about six inches below the level at which Granby artifacts are no longer found. After Granby died out is when this area began to be plowed. Could this have been a wood post for a Granby building or Thomas Brown's log cabin trading post? A six-inch plow depth (at the Granby level which is almost two-feet below today's surface), would explain the post being at the level we found it.

As the excavation continued, it became apparent that this was not a tree or stump because there was no sign of roots. When we finally pulled it out, we began to realize this was a squared-off post with a diameter of about 22 inches and a length of about 21 inches. We would later discover that this post was exactly in line, perpendicular with the Congaree River, with a post hole (14 feet away) we found in pit 43 over seven years ago. The post position was also in line (90 degrees) with another hole feature we found in pit 113, about six feet away.

One last mystery about the post is that it has termites in it. Not very many of them, but several can be observed on the surface. How could a piece of wood like this have lasted for over 275 years with termites eating it? One explanation may be that the corner of the pit where the post was found is next to the corners of two pits (pit 67 and pit 69) that we dug in 2014. Maybe those excavations opened an easy (uncompacted) path for termites to travel. As well as moving our Finding Granby project into the preservation of iron objects (electrolysis), now we have to figure out how to try and preserve a possibly 275-year-old piece of wood.

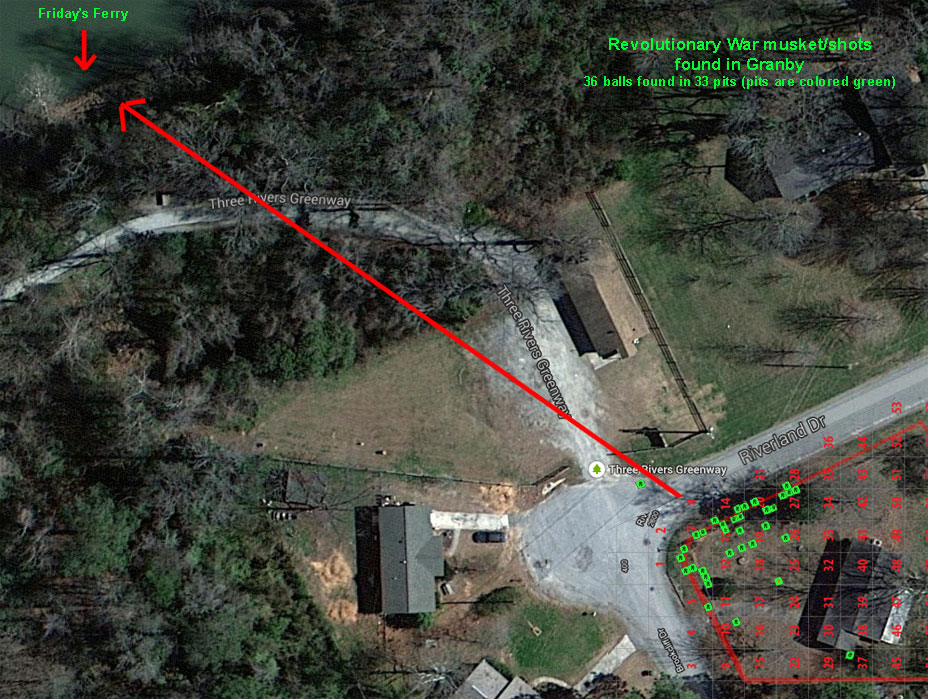

Number 20: Multiple Pits -

Musket Balls/Shots

A significant number of pits have given us lead balls that

range in

size from .19 to .60 caliber. Just a few hundred feet away, on May 1,

1781, "South Carolina Patriot militia Lt. Col. Henry Hampton attacked

the British detachment guarding Friday's Ferry. Hampton's men killed 13

of them. Hampton then attacked another small detachment on their way to

Fort Granby. Another 5 were killed in this action and Hampton captured

a number of horses and slaves." Some of these balls could also be from

before the Rev War like from the hunting of early traders like Thomas

Brown. There is even the possibilty that some balls could be from the

Civil War. You can learn more about

the musket balls/shots found in Granby at this link.

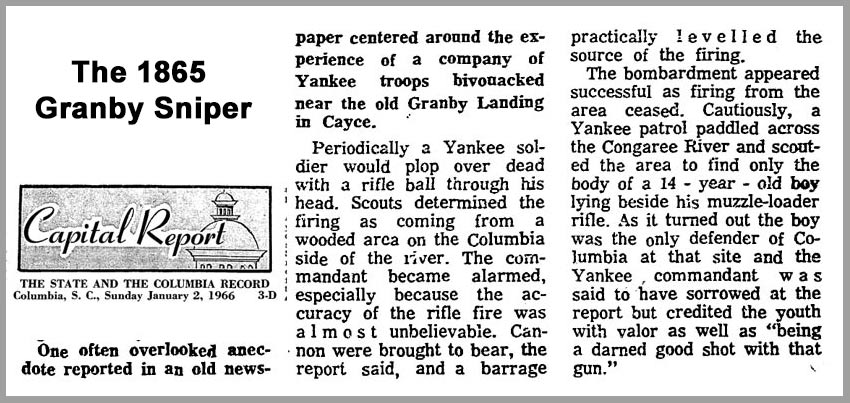

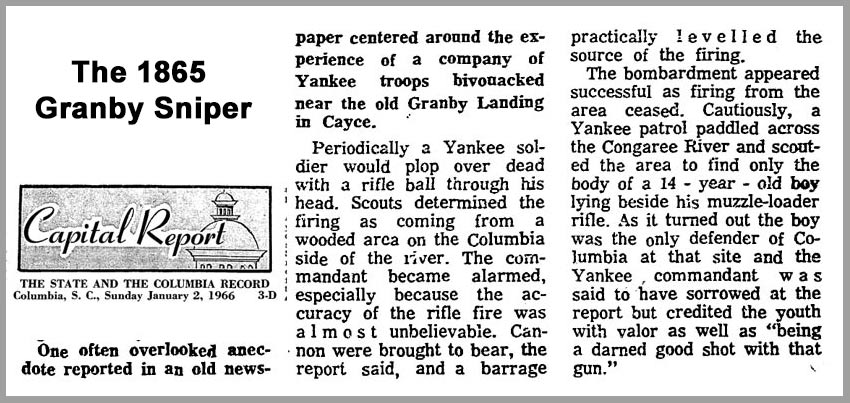

Number 21: Pits 34,94,

and 97 - Civil War Finds

Possible Civil War artifact finds in Granby include a bullet,

shell, gun barrel, and Prosser button. The button post-dates Granby and

was likely from the undergarment of a Union soldier. General William

Sherman mentioned camping in Old Granby shortly after the Battle of

Congaree Creek and the following newspaper story raises the possibility

that some of the lead balls we have found could be from this 14

year-old Confederate Granby sniper. Keep in mind that, in the 1800s,

"Granby Landing" was the old site of Friday's Ferry. It was not the

site of today's Granby Landing which is 1 mile south.

You can learn more about these Civil

War finds at this link.

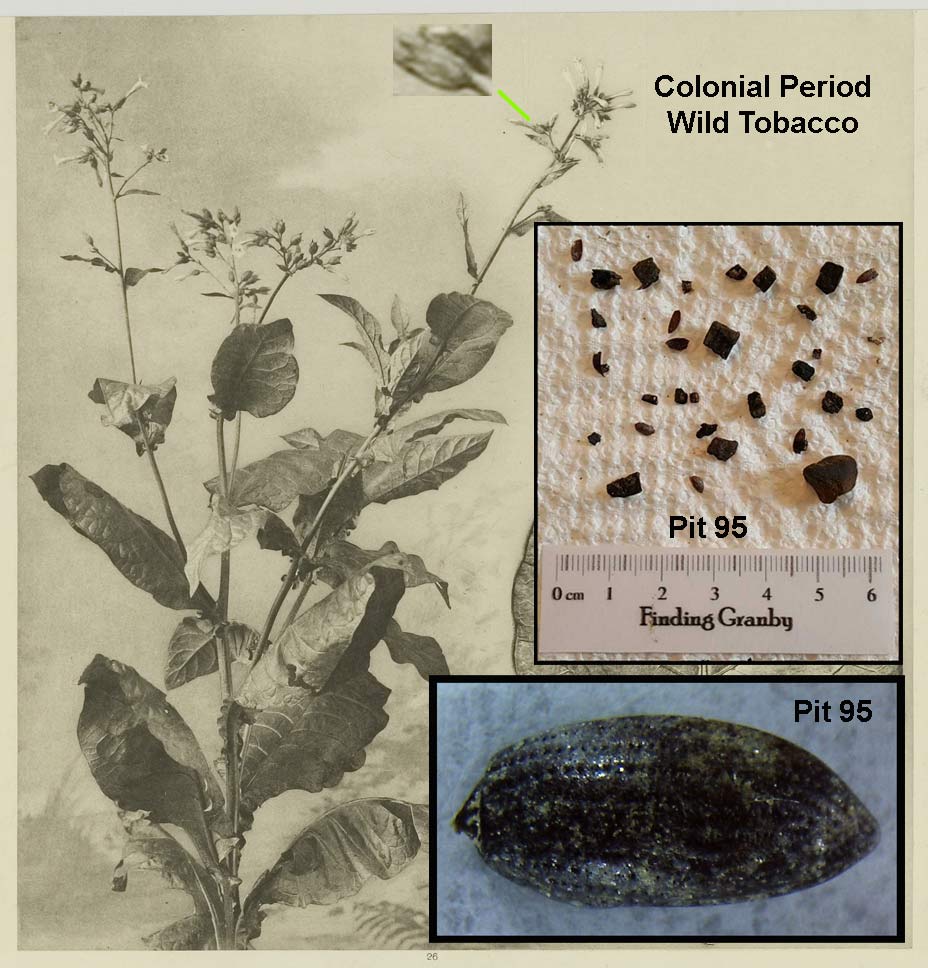

Number 22Pit 95 - Ancient

Peace Pipe Tobacco

The biggest find pit 95 would not unfold until the next day

after

cleaning. Not much notice was given to a small charcoal deposit in

level 3 but, nevertheless, it was carefully excavated. Later on, after

more care in the cleaning, tiny insect or seed like pieces were found

in the charcoal. Microscopic examination and some expert evaluation

seemed to indicate that the items are tiny burned seed pods. A lot of

time was done researching this and the best guess is that this was the

very young flower seed-pod of a tobacco plant. The amount of charcoal

we found was, in fact, just about what you would expect to come out of

a smoking pipe. Europeans only used the tobacco leaves for smoking but

Native Americans were known to smoke these flower/pods in ceremonies.

"Instead of pinching off the tobacco flowers to make the leaves grow

bigger, American Indians harvested the flowers (before they went to

seed). The most prized smoking tobacco was that made from the flowers.

Buffalo Bird Woman related to an anthropologist how the Indians made

smoking tobacco, from planting the seed to final cure."

The

careful excavation of the charcoal that was with these tobacco seeds

could, through Radio Carbon Dating, give us a date for this Native

American event. You can learn more

about the ancient tobacco find at this link.

Number 23: Pit

8, 46, and 62 - Granby Beer/Wine Bottles

This find involves three bottle pieces. One bottle top from

pit 62

which had just the right shape and size to match a green bottle from

1800. It's better, however, if you can also get a bottom piece of the

bottle which we did with the bottle top found in pit 8 and a bottom

piece found in pit 46. The unique combination of the top and bottom

design of an old bottle makes it possible to confidently date a bottle

type to about 5 or 10 years. The shape of our pit 46 bottom piece is

similar to several bottles between the years of 1761 and 1809 but, when

you look at the bottle top (same type of green glass) it narrows it

down to just the 1804 bottle. The mouth design and size (outside

diameter of 1.5") are the same and, maybe even more unique, is the neck

piece. The neck is not curved like most bottles and the angle it takes

is just like the 1804 bottle. Furthermore, the 1804 bottle was one of

the few wide bottles shown in the artifact drawings. The drawing shows

it to have a base diameter of just a little less than 4 inches. The

base piece we found had a perfect curvature outline on the inside of

the piece. It was difficult to measure but we finally took a digital

image of it and processed the image to extract this curvature outline.

A complete circle was drawn to match the curvature and the diameter of

the circle ended up being 3.85 inches. It was a fat bottle matching the

base measurement of the 1804 bottle! This is a very important find

because it's the first real date we have on this green bottle glass

which we are finding in about 75% of the pits. In this case, 1804 would

point to the owner of our Granby House: Samuel Johnston whose family

lived in Granby from 1790 to 1815.You

can learn more about the at this link.

Number 24: Pit 86 - Thomas

Brown Beer/Wine Bottle

Similar to the Granby bottle finds, pit 86 gave us two bottle

top

pieces and a bottom piece. From the curvature of the bottom piece, we

measured that the bottle would have had a 4.5" diameter at the bottom.

The two top pieces gave us an almost complete bottle top and we were

able to match this and the bottom piece to bottles made between 1739

and 1751. This is a little too early for Granby so it must have

belonged to the previous land owner: Indian trader Thomas Brown and his

Catawba wife.You can learn more about

the Brown bottle at this link.

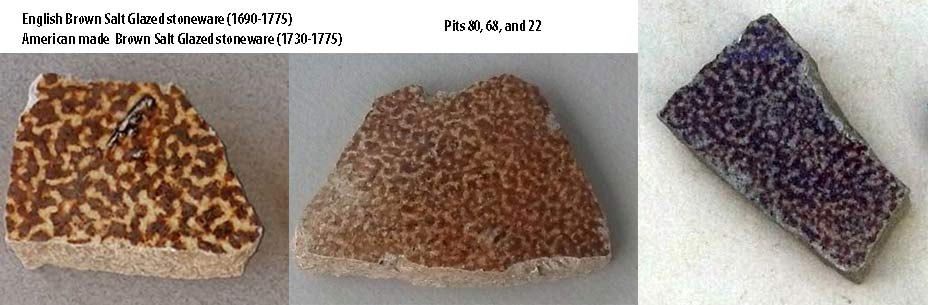

Number 25: Pit 22, 68, and

80 - Brown Salt Glazed Stoneware

This very easy to identify stoneware type was made in England

from

1690 to 1775 and made in America starting in 1730. This is a special

item because it could cover both the Thomas Brown period and the early

Granby period. One piece from pit 68, however, has a distinct

difference. It is not glazed on the inside. This could mean that it was

an early american form of the Brown Salt Glazed Stoneware and, very

likely, belonged to Thomas Brown. You

can learn more about this possible Thomas Brown item at this link.

Number 26: Multiple Pits

- Buttons & Buckles

It would not be a Colonial period dig site without these

items. All

of them them are Granby period with the exception of the Prosser button

(white button) which is Civil War period. Learn more about the Buttons and the Buckles at these links.

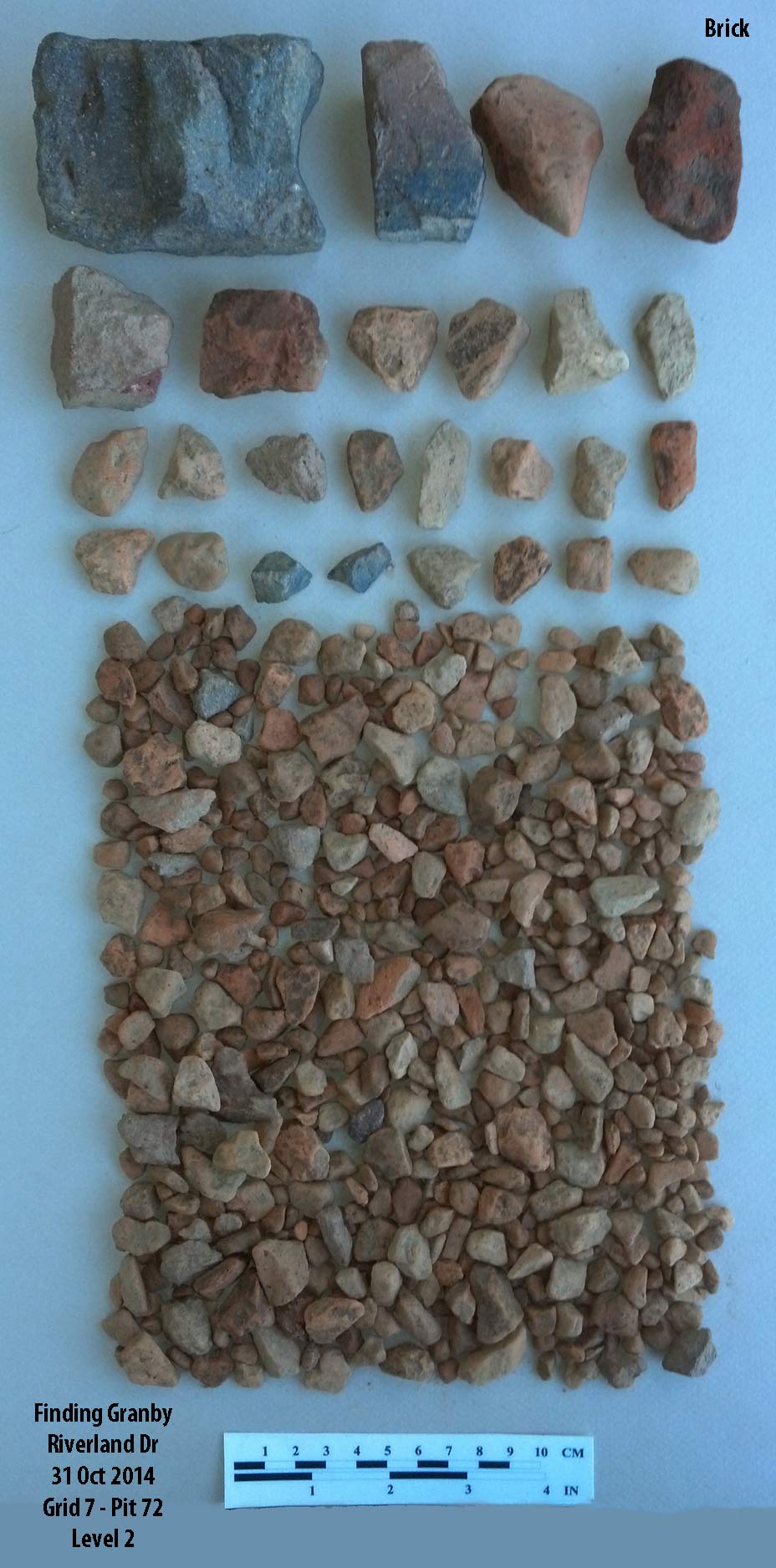

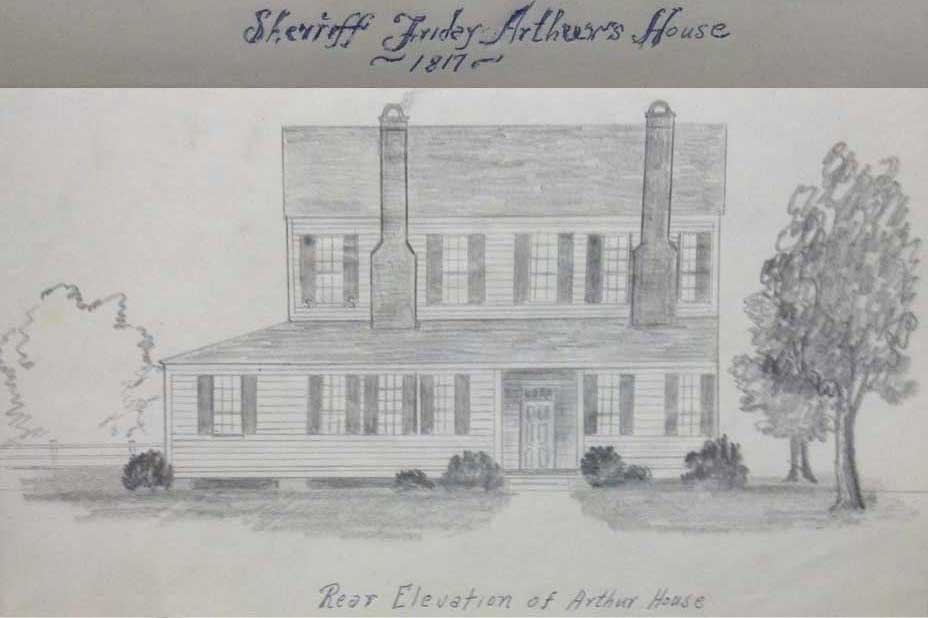

Number 27: All Pits -

Granby Brick

Brick is a very common item we find in Granby. From very

small

"Granby gram" pieces to a full standard Colonial period size brick.

It's standard in South Carolina Archaeology to not count brick pieces

as artifacts. If we did, our artifact total would probably quadruple.

We do, however, weigh the brick pieces per pit and use this (along with

nails, window glass, and post hole finds) to determine where a Granby

building had been located. In Granby, bricks were mostly used as the

foundation segments and fireplace/chimney like seen in the 1817 drawing

of the Friday Arthur house in Granby. The brick that made up the inside

of the fireplace may have been the grey color pieces that we find which are either burned or they were made with a different type of clay. These grey pieces are very hard which allows it

to survive in larger pieces. Other brick became soft and were broken up

into small pieces by plowing of the land.

On October 7, 2021, the Cayce Historical Museum hosted a very informative talk by Historic Camden's Cary Briggs on brick-making. Did you know that sand is what gives strength to bricks? When a brick is over-fired, that sand will come to the surface as a glass (glaze.) I brought some samples of bricks we found in the Granby dig to have Briggs examine them. Most of our brick finds are "salmon-colored" small, fragile pieces that Briggs said were of low-quality production. He pointed out that a building like Fort Granby-Cayce House (today's Cayce Historical Museum is a replica of that) would have required about 60,000 bricks just for the two chimneys. That's about 5X what today's chimneys would use. That's 1.5 to 2 million pounds of bricks, which would be about five full truckloads of bricks today. Because of the weight involved, in 1780, these bricks had to have been produced on-site (in Granby.) Briggs also pointed out that there is no better place to find good clay than in the Midlands. He then explained to us the labor-intensive (but relatively simple) process of making bricks. The kiln itself was made out of the bricks that were to be fired. He brought a pre-fired brick (left to dry for about a week after molded) and a fired brick. I could not tell the difference (the feel or the appearance) between the two. But, the pre-fired bricks have more moisture in them and will not last long without being fired. So, for our Granby dig project, we now know where most of the brick artifacts came from. We do, however, also find a very strong brick that has a consistent grey color. These were probably made with a lump of completely different clay and by professionals. Our cheaper bricks were probably made, on-demand, by the Granby slaves who normally did other types of work. Historic Camden has a bunch of brick-making activities coming up. You can find out more at:

Historic Camden Brick-making.

Number 28: Pit

107, 110, and others - Glazed Brick

TBD

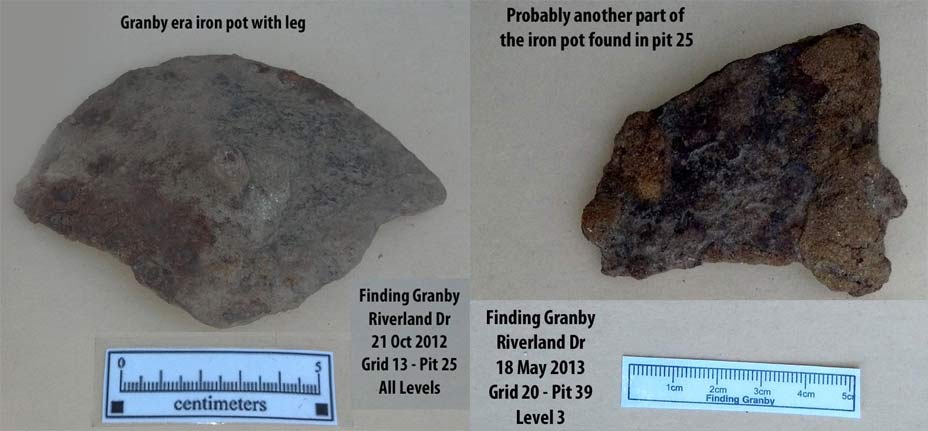

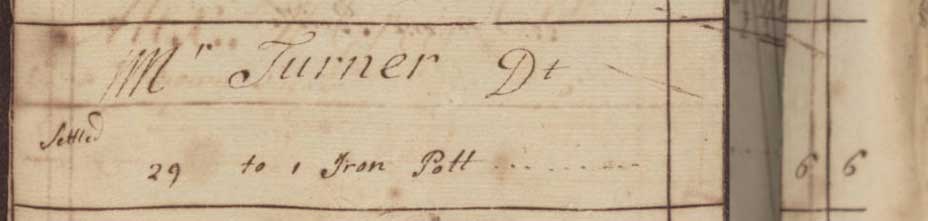

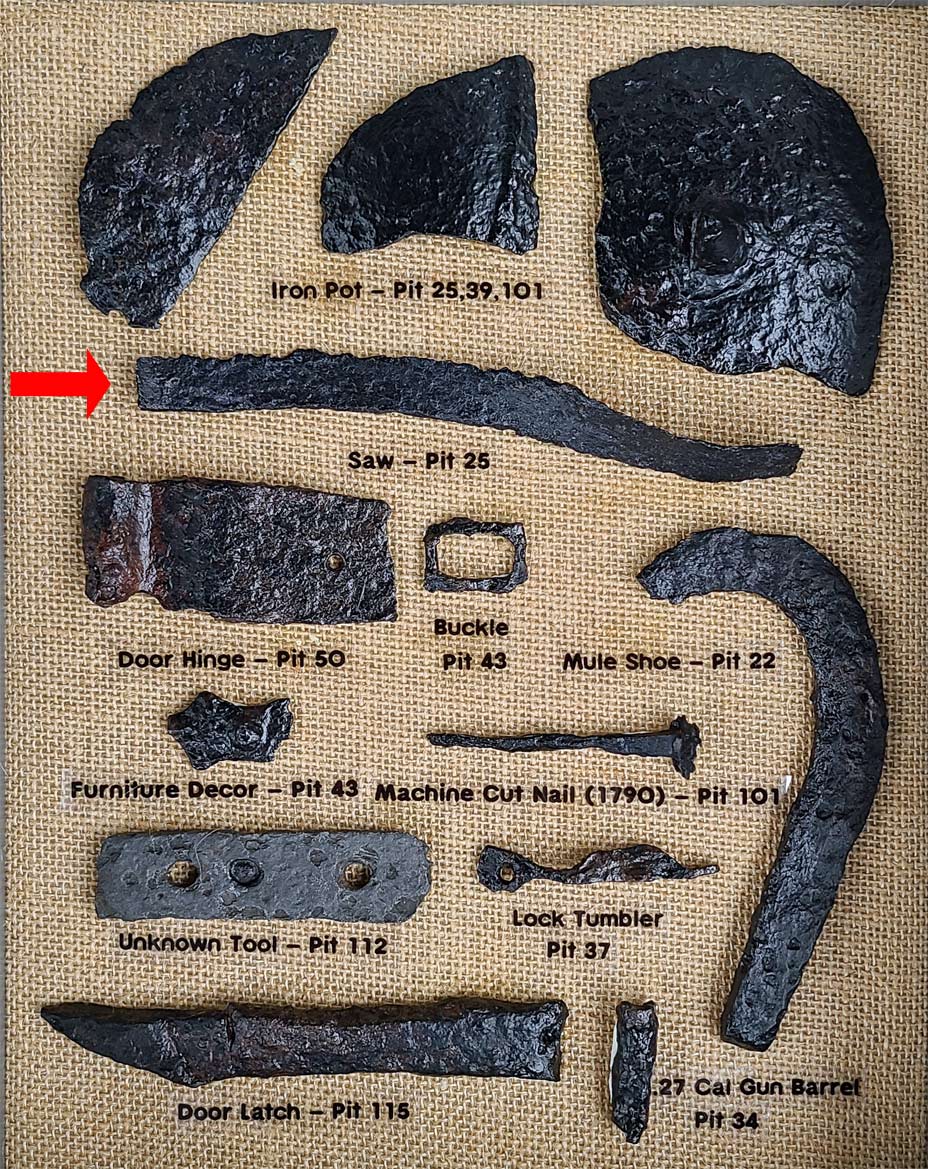

Number 29: Pit 25 and 39 -

Iron Pot

At the time of this find in pit 25, this iron pot piece (with

a

leg), was our largest artifact and was verified by the South Carolina

State Archaeologist. Pit 39 would give us another piece of the pot. The

Congarees Store account book also showed a similar item bought by a Mr.

Turner in 1784. You can learn more

about the Iron pot find at this link.

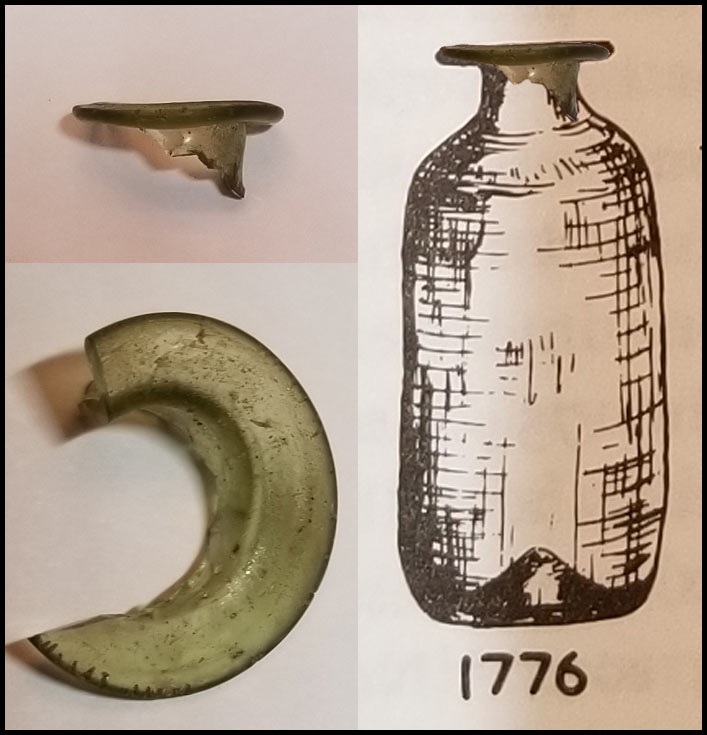

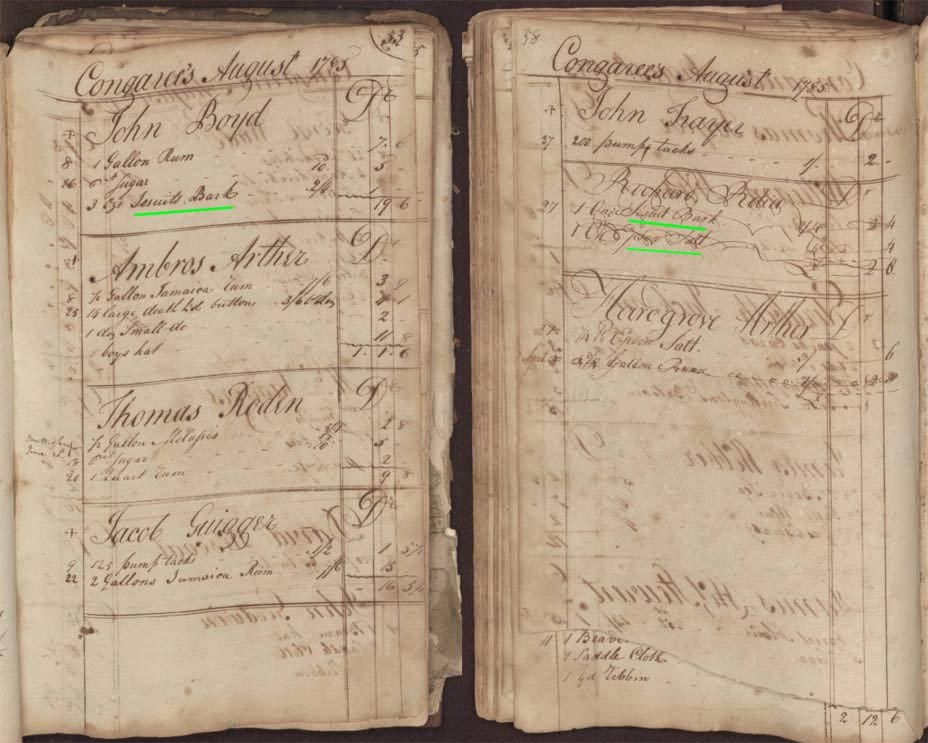

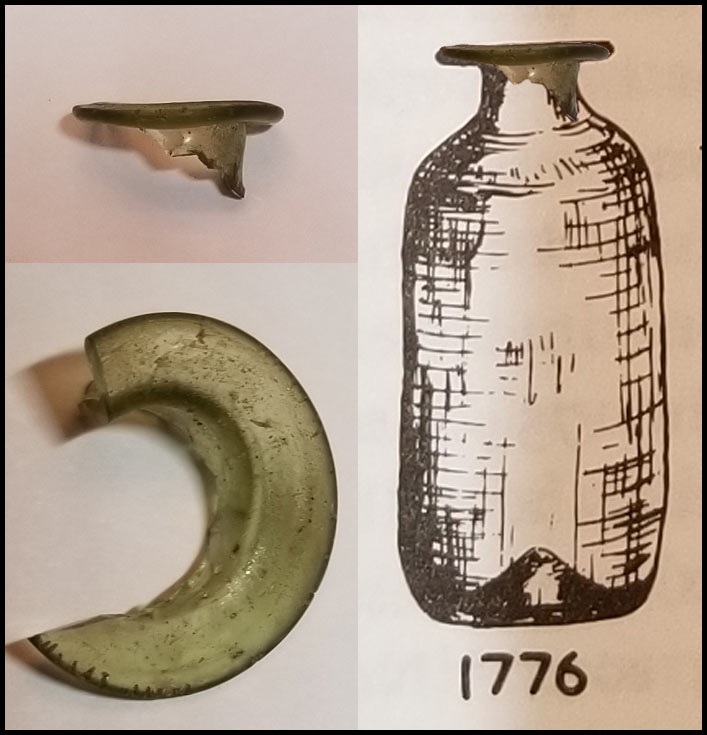

Number 30: Pit 108 - Medicine bottle top for Jesuit's bark

Pit 108 gave us the unique top of a 1776 2.5 inch medicine bottle. During the period of Granby, this was the typical bottle used for the sale of Jesuit's bark powder.

Jesuit's bark, also known as cinchona bark, Peruvian bark, or China bark, is a former remedy for malaria. This is more evidence of the "unhealthy" enviorment of Granby, which we now know was caused by mosquitoes. The bark contains quinine which is still today, used to treat malaria. The bark is indigenous to the western Andes of South America. It was discovered as a folk medicine treatment for malaria by Jesuit missionaries in Peru during the 17th century.

There are many personal purchases of bark in the Congaree Store for customers like John Boyd, Richard Relia, Benjamin Grubb, Gabriel Ragsdale, and David Renolds.

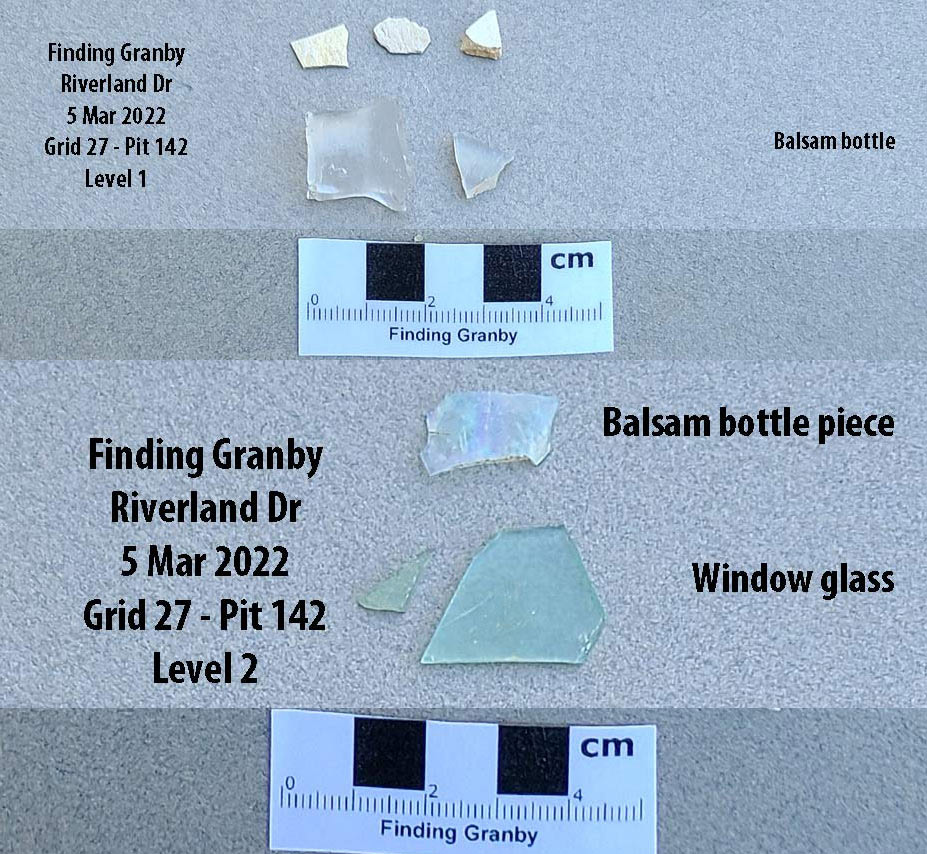

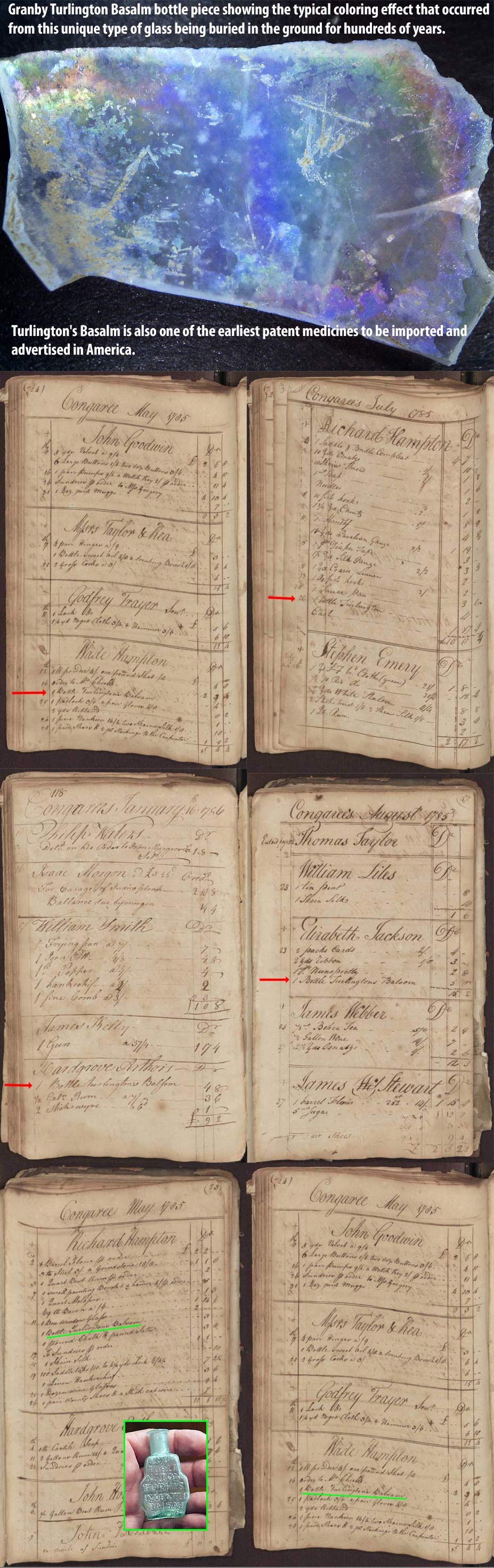

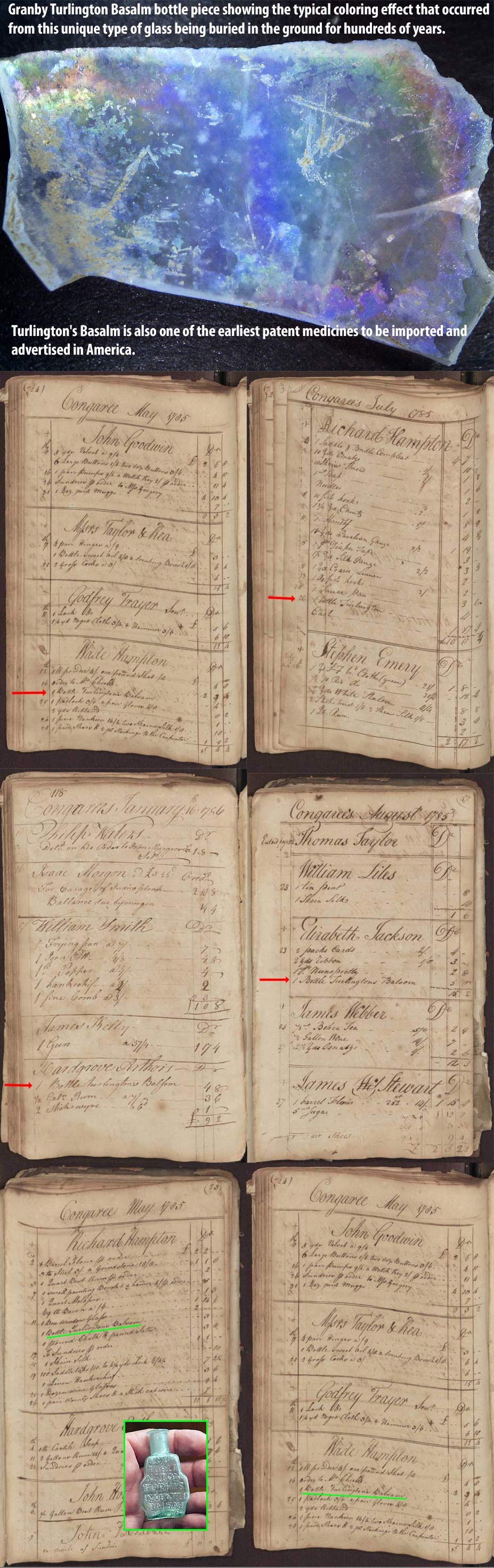

Number 31: Pit 142 - Turlington's Balsam of Life Bottle

The Granby dig team discovered a new type of glass in pit number 142. We measured the curvature of one of the pieces, and it matched the diameter of the neck of a Turlington bottle.

Turlington's Balsam of Life was a medicine patented by Robert Turlington in 1744. Turlington obtained his patent for the medicine's production from King George the second, making Turlington its exclusive manufacturer. With its 27 secret ingredients, Turlington claimed the medicine would successfully treat a wide variety of illnesses, including "kidney and bladder stones, cholic, and inward weakness."

The most distinguishing feature was the rainbow color of the glass artifacts. The glass of the old Turlington bottles tends to have a chemical reaction when left in the soil over many years, giving the glass a rainbow color. The reaction is caused by the interaction of the patina and the chemicals used in creating opalescent glass. This unique and rare effect leaves little doubt that the glass pieces of Granby pit 142 are from a Turlington bottle.

The patent that Robert Turlington had enabled him to specify who sold it. It made its way to the Congaree store through Charleston.

The store's biggest customers, by far, were Richard and Wade Hampton, and they also purchased the most bottles of Turlington. We don't know what their specific ailments were, but they made multiple purchases over a period of six months in 1785. The purchases stopped after that, so we can guess that the Hamptons were not impressed.

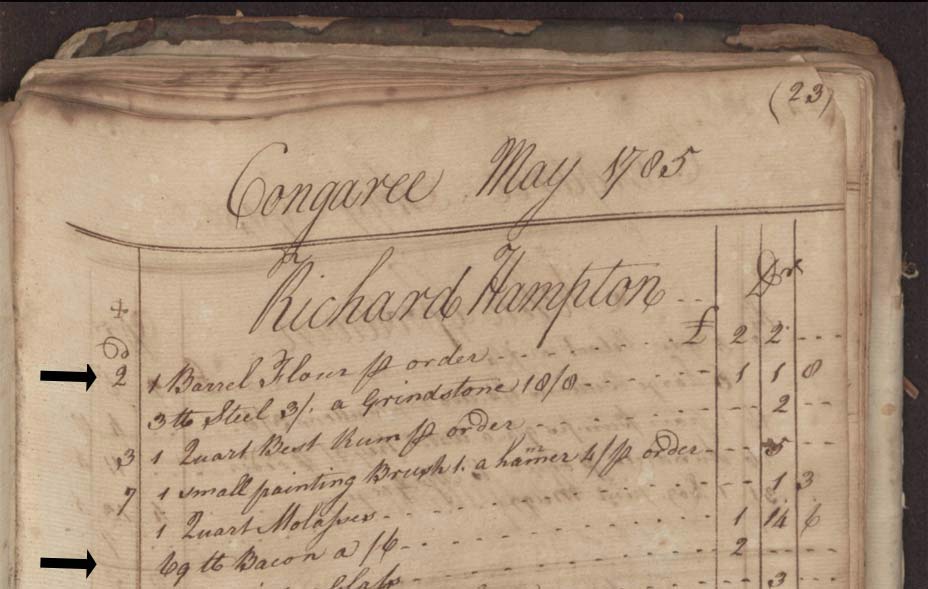

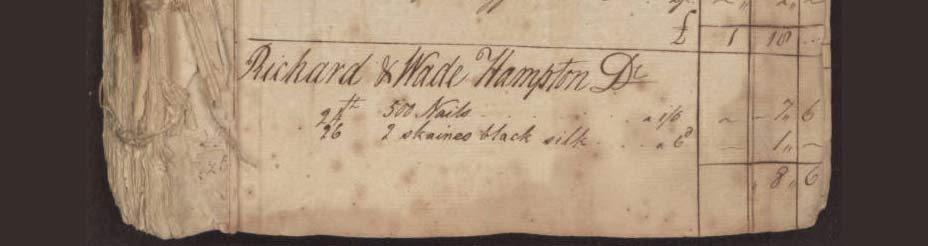

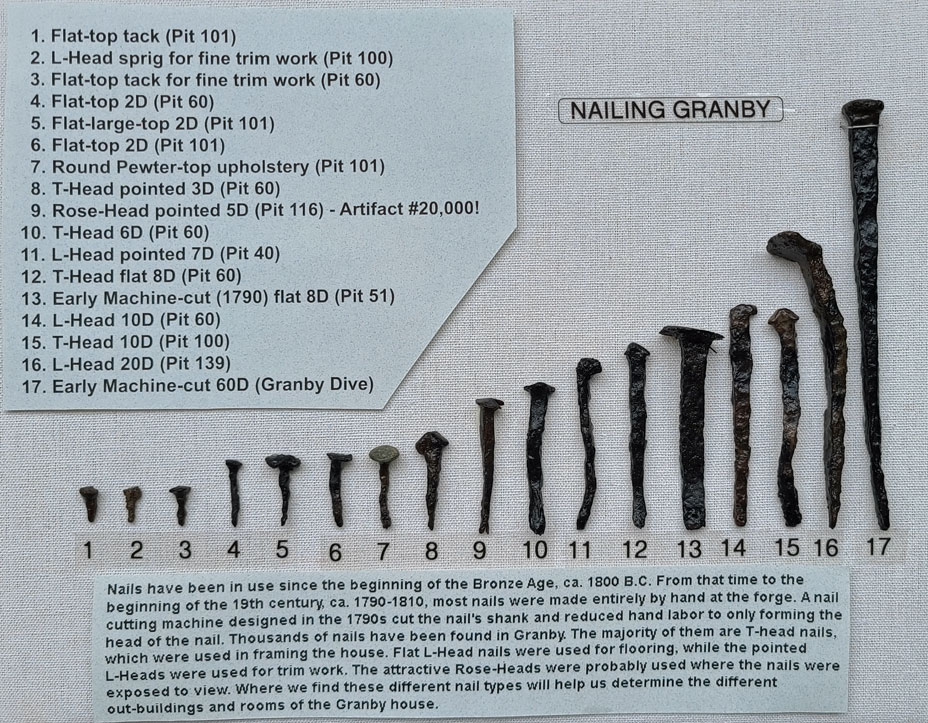

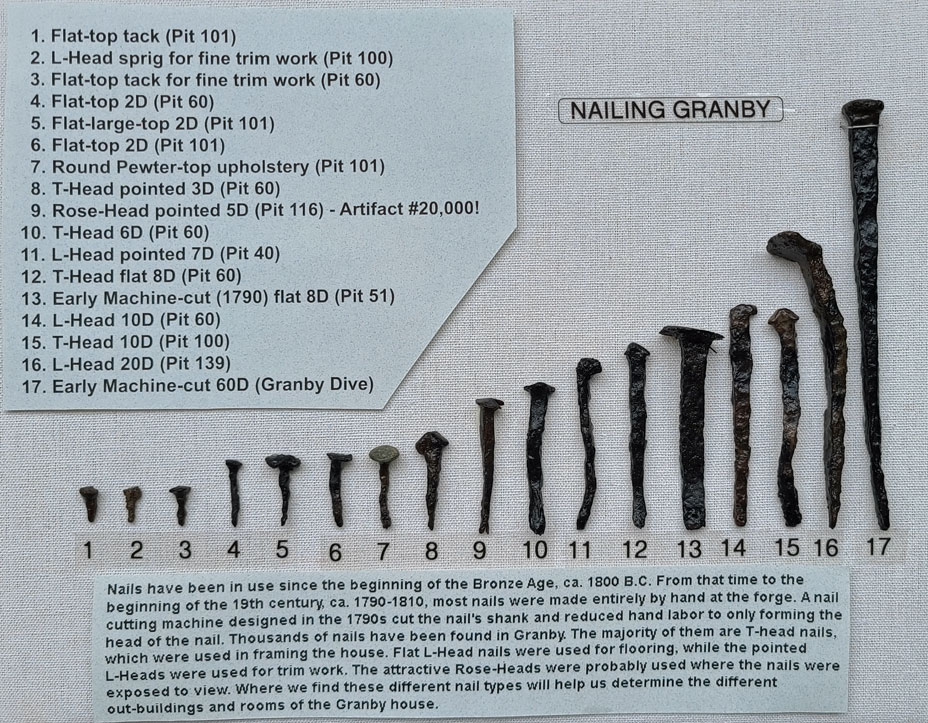

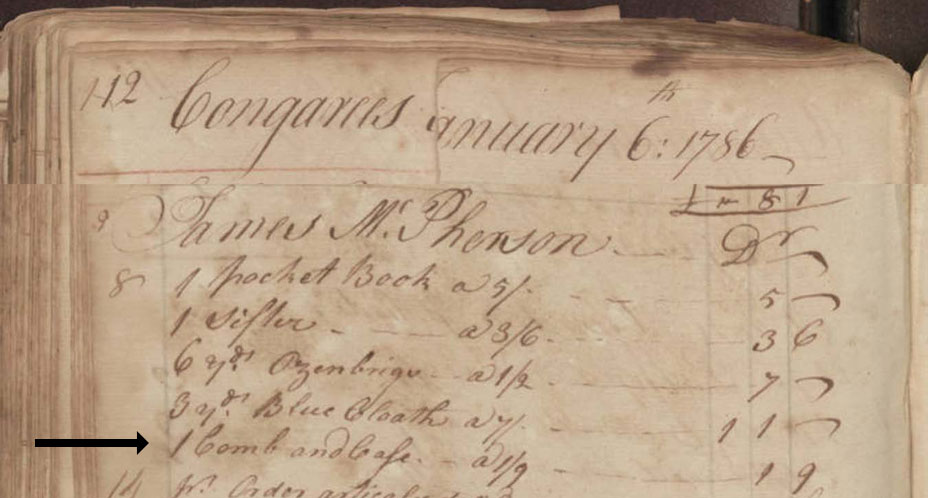

Number 32: All Pits: Hand

made nails

Hand forged nails represent 11% of the artifacts found in

Granby.

They come in several different types: T-Head, L-Head, and Rose-Head.

They are all hand wrought and square which means they were made before

1800. The above image of the 1784 Congarees Store (in Granby) account

book shows where brothers Wade and Richard Hampton bought 500 nails. We

believe the Samuel Johnston house (which we are digging) was built

around 1784. Maybe the Hampton's were the builders and we are finding

some of the nails they bought over 230 years ago. Almost all the nails

we find are rusted but about 1 in 600 are not. We got a good appraisal

from the South Carolina State Archaeologist (Dr. Jonathan Leader) of

one of these pristine nails found in pit 92. The lack of rust was

because of a protective coating that naturally occurred in the process

of creating the nail. But, that would only last if the nail remained

undamaged. Dr. Leader further explained that after shaping/cutting of

the nail, it was dipped in oil. He said the oil can still be seen on

this nail. He said it was a flooring nail. Folded at 1 inch means the

wood was 1 inch thick. Dr. Leader said that holes were probably drilled

which is why the oil was not lost on the nail when it was put into

place. That's how a nail in the ground can avoid rusting for hundreds

of years. Check out this link on pit

60 where we found 49 Granby nails.

Below is a display that shows the different nails that have been found in the Granby dig.

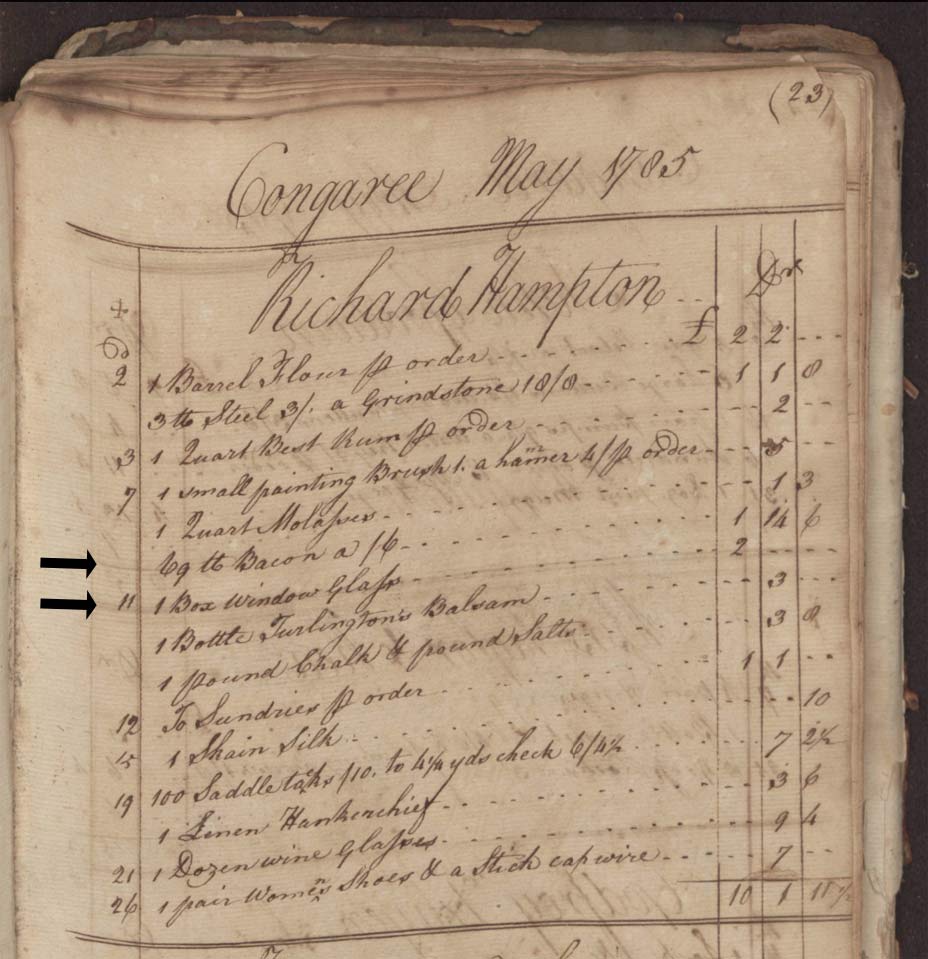

Number 33: Pit 93 and most other pits - 18th Century Window Glass

Yet another sign of the wealth of Granbians.

Window glass was an expensive commodity during our Colonial period. According to the Congarees Store account book, in May of 1785, Richard Hampton purchased a standard size box of imported window glass and 69 pounds of bacon. This amount of pork could provide enough protein for an adult for one year. That 50-pound box of window glass costs 20% more than the pork and would only be enough for filling four windows. Window glass was so expensive that it was tax accessed separately from the house.

In the 18th century, broad glass and crown glass were the two primary types of window glass. It isn't easy to distinguish between the two. About 3700 pieces of window glass have been found in the Granby dig. The thickness of our glass varies between 0.4mm and 0.9mm, with the average being .7mm. The variation in glass thickness has to do with the way the glass was made. The smallest piece of glass shown in the display is the thickest (0.9mm), and it has the characteristics of being part of the rim. This rim discovery and the wide variation of glass thickness almost certainly means that our Granby glass was the more expensive crown glass.

"To make crown glass, a bubble was blown and then cut at one end; the resulting cone was spun on pontil rod, causing the glass to spread out into a circular sheet. Because it cooled while still suspended in air, crown glass was clearer and more brilliant than broad glass; consequently, it was the more desirable and the more expensive type of glass. The circular sheets could vary in diameter from 2 to 5 feet, with 3 or 4 feet being the most common size in the eighteenth century. The panes that could be cut from the disc were limited in size by the thickened rim and the thick "bull's eye" in the center, where the glass was broken from the pontil rod. The bull's eyes were sometimes discarded, but they were also used in more poorly constructed houses or where good visibility was not required. It is not always possible to distinguish between the two types of glass from excavated examples. Sometimes, crown glass is found with part of the rim or bull's eye attached, which makes identification certain. Such glass found in Williamsburg is generally blue-green in color, only slightly decayed, and occasionally has curved lines of bubbles or stress marks. Identical glass, when found without the rim or bull's eye, also may be assumed to be crown glass. In contrast, much of the broad glass found is of a pale grayish-green color."

Number 34: Pit 43 - Cloth

with Indigo dye

Finding cloth deep in level 3 of pit 43 was a big surprise.

All the

other artifacts from the level were Granby and Native American. It is,

however, possible for cloth to survive in the ground for hundreds of

years. The cloth pieces had the obvious color of Indigo blue which was

very common in Granby. In 1968, Gladys N. Chambers wrote the book: "The

History of Cayce, South Carolina" and noted the following about Granby

Indigo. Was Indigo another reason for the downfall of Granby?

"The indigo plant had been first brought to North America

into South Carolina in 1742 by Elizabeth Lucas Pinckney, and had become

one of the main home industries of this area. Millions of pounds were

also shipped to the dye plants in Europe. Sometimes the plant grew

wild, but as a chief source of income it was cultivated. The ground was

plowed near the end of the year, and some mulching done. In the

following spring the seeds were sown. The plants were cut two times

each year, once in the early or midsummer, and the second time about

two months later. The dark blue dye was used in calico printing and

dyeing, also for other materials."

Chambers later notes:

"The last record found of Granby as one of the LEADING

TOWNS of South Carolina was in 1815. Rumors of mosquitoes and a low,

sandy place were circulated when the talk of changing the Capital from

Charles Town to some central place was in progress (in 1786). This had

its effect on the popularity of the town. Many of the Granby people who

grew indigo plants were building summer homes in other places, because

of the many mosquitoes. The water used in making the dye for home use

became stagnant and thus bred millions of mosquitoes." Check out the many cool items found in

level 3 of pit 43 at this link.

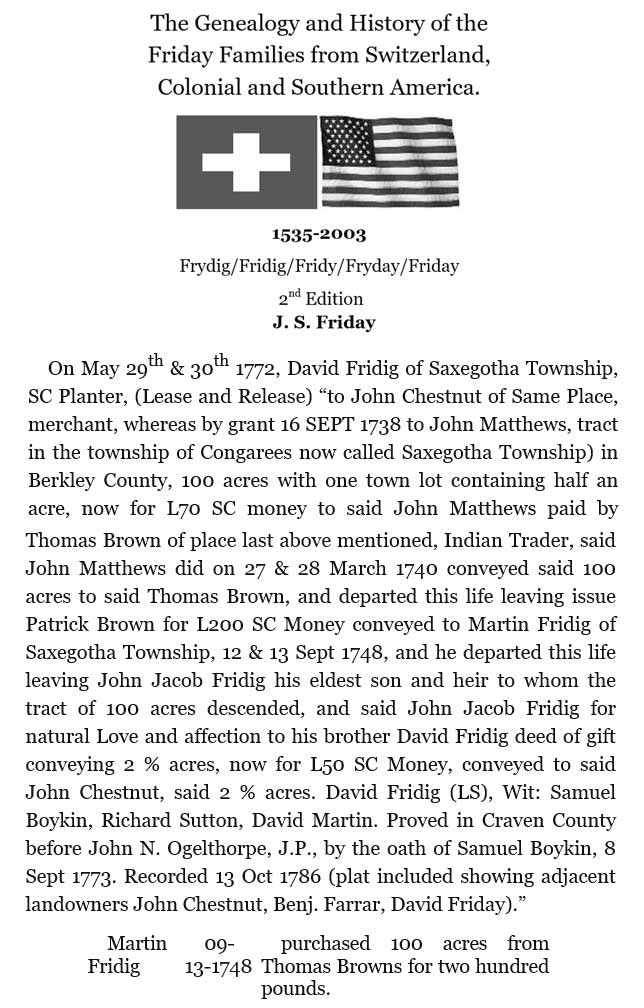

Number 35: Archival

- Location of Thomas Brown property

Several of the previous top finds have mentioned the theory

that,

prior to Granby, trader Thomas Brown lived on the Granby dig site. Many

artifacts have been found which place him at this location between 1740

and his death in 1747. Part of our Granby research has been genealogy

and the building of family trees of the people who lived in Granby.

This discovery was made by members of the Friday family doing their own

genealogy work. They found the following index to a title chain in the

South Carolina Archives under: Series: S111001, Volume: 0006, Page:

00074, Item: 000, Date: 4/11/1763. They pulled the microfilm that gave

the details. In our building of land plats, we already knew that John

Mathews had the original land grant for the property of our dig. The

Friday family discovery shows that Thomas Brown bought the property

from John Mathews in 1740 and it went to Brown's son after Thomas'

death in 1747. This leaves little doubt that Thomas Brown did live on

this land and probably carried out many trade transactions here as

indicated by the trade and Native American artifacts we have found

here.

Side note: The discovery of Fort Congaree II (shown in

the above land plat overlay) also gives more proof to Brown's property

location. The adjacent Fort Congaree II property and Brown's property

shared the same pond. Elevation mapping of today shows the pond is

still there today although it only fills with water (to the dismay of

Riverland Park residents) when the river is high.

See more about the Granby

land plats at this link. Learn more about the people who

lived in Granby at this link.

Find even more about the people who lived in Granby by clicking on places

in Sarah Friday's 1810 drawing of Granby at this link.

Number 36: Most

Pits - Native American Pottery & Tools

Native American artifacts represent about 3% of the artifact

total

in the Granby dig. The period from Granby until modern times (270

years) is very short compared to the time Native Americans have been

here (12,000 years). So why don't we find more items from the Natives?

We would find more if we dug deeper since older items are buried over

time because of the cycles of plant life that die and turn to dirt. In

this area, ants are also responsible for moving dirt up which covers

items on the surface. Of the Indian items we find, pottery is the most

common followed by tools. This mosaic is an example of some of these

items we have found in the Granby dig. Learn more about Native

Americans in Granby.

Number 37: Pit 22 -

Carpenter's Ruler

This is an example of making a bad first guess on an

artifact. We,

originally, thought this might be the brass pivot mechanism of a Civil

War era pocket knife. It really didn't seem possible, however, that the

blade could have been attached to this with the strength you need in a

knife. Dr. Leader (South Carolina State Archaeologist) immediately

recognized it as the part of a possible Granby era Carpenter's ruler.

Now that made more sense and this picture of an antique ruler from

London confirms it. Check out this

and other finds from pit 22 at this link.

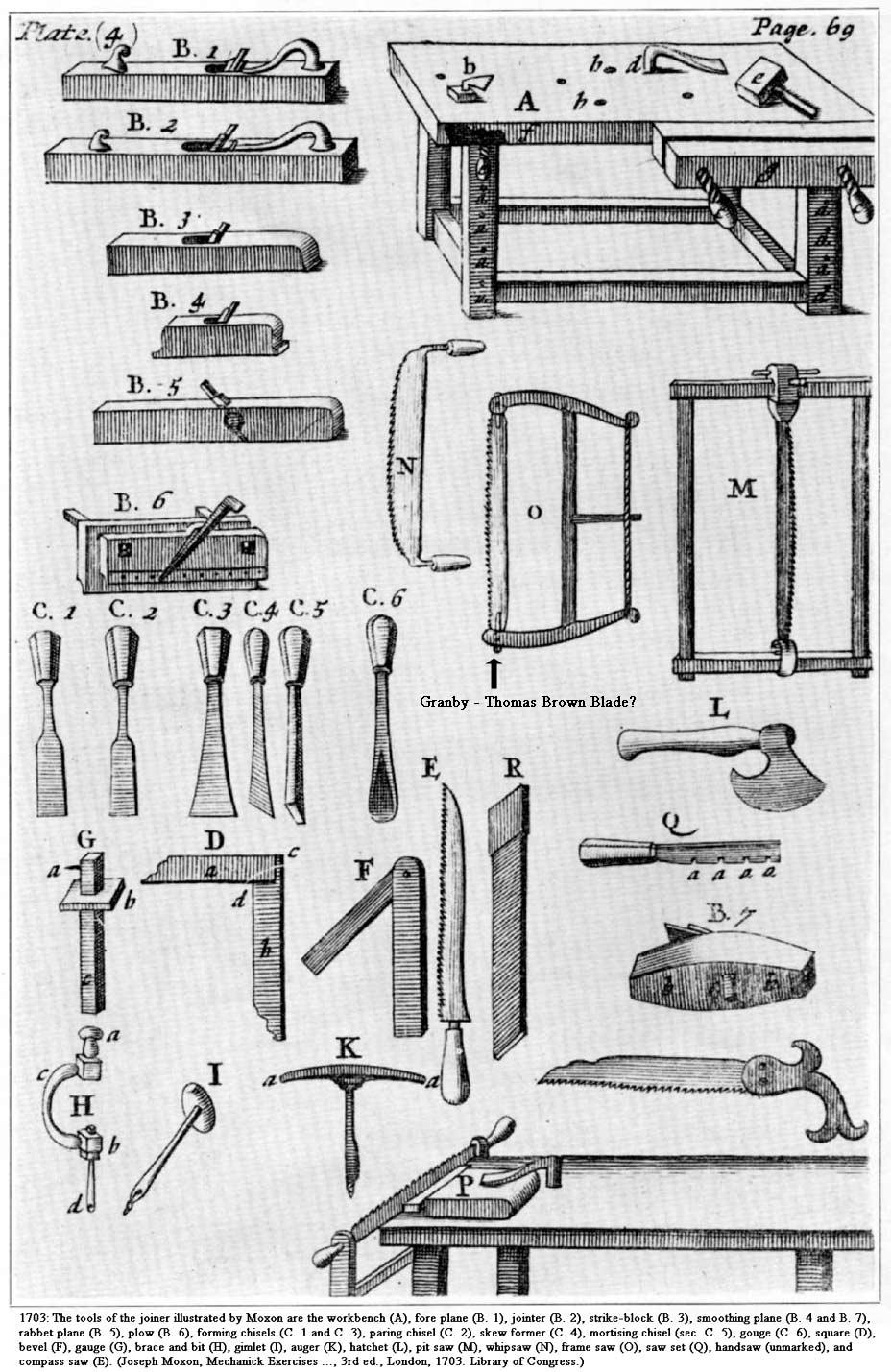

Number 38: Pit 25 -

Saw

Yet another item that took a number of years to figure out. While cleaning select Granby iron items (electrolysis), for the above museum display, a mystery item gave its secret. After cleaning and magnification, this twisted strip of iron turned out to be a saw blade, possibly even one that belonged to Indian trader Thomas Brown.

Number 39: Pit 29 - Gator

Bowl (pipe bowl)

We found a record 4 pipe stems (dated: 1720-1750) in pit 29

and, at

the time, our largest pipe bowl piece. This decorated piece doesn't

look like much until you turn it the right way. Sir Walter Raleigh and

gator/croc clay pipes were popular in the mid-17th century. "The

English were the first to make tobacco a consumer product. Sailor,

explorer and writer Sir Walter Raleigh (1554-1618) is considered the

one who popularized smoking. Thanks to him, it became fashionable in

the court of Queen Elizabeth I, and soon spread to high society

throughout Europe. The first commercial operations appeared, initially

in Holland, in 1561, and later in Germany. Legend has it that Raleigh

fell overboard off the coast of Virginia one day. He was seized by a

crocodile, but the animal found the smell of smoke so repugnant that it

released him! A series of pipes was produced bearing the likeness of

this "hero" sometimes with crocodile included."

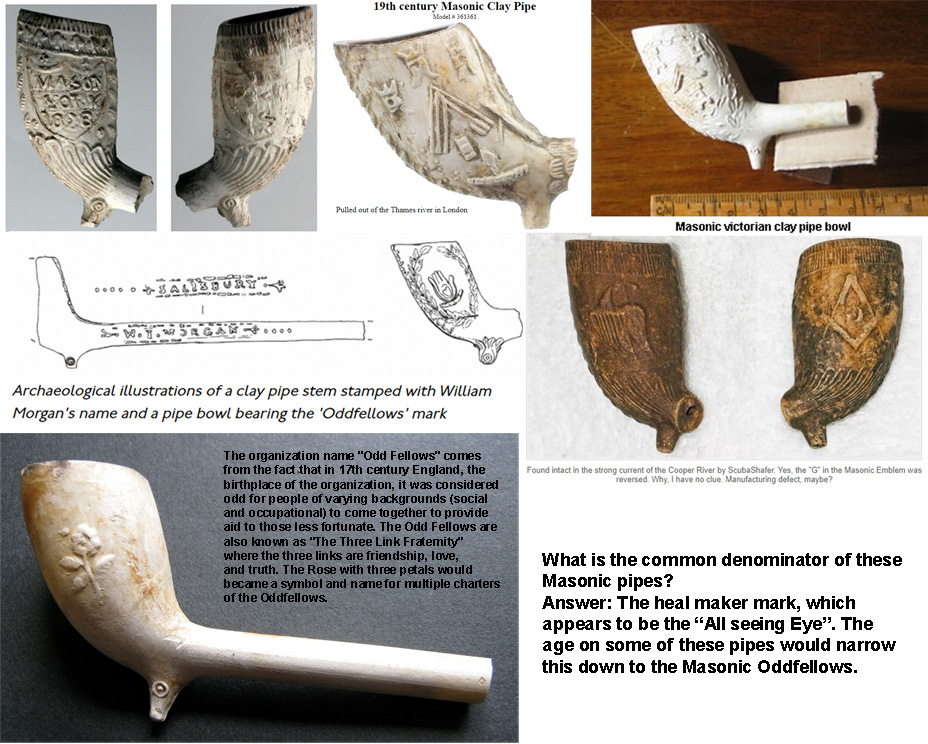

You can see more cool finds from pit 29 at this link.

Number 40: Pit 14 -

Odd Artifacts in an Artifact

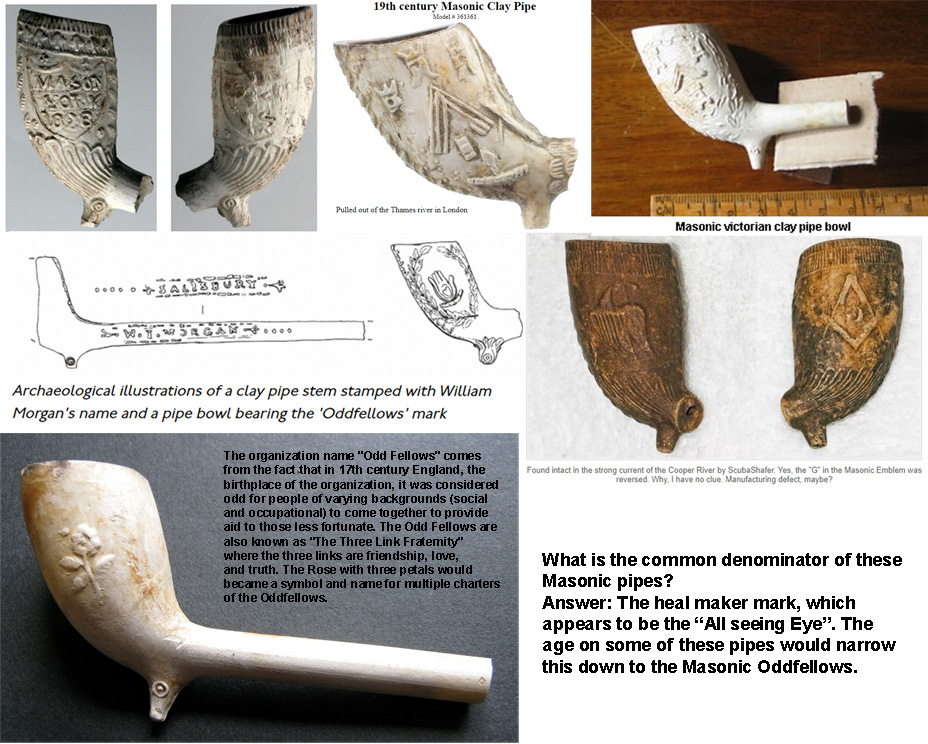

Another late discovery. It took over seven years to begin to understand this item. After going through dozens of pipe historical papers/books and hundreds of photos, it seems this is something clay pipe historians have completely missed. Granby had three generations of Alexander Bell which spanned 100 years (1752-1852.) The second Alex was a Freemason.

One in six of the signers of the Declaration of Independence were Freemasons. They included George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Paul Revere, and John Hancock. By 1812, one in 12 people in the United States were Freemasons. By 1860, this had increased to one in eight. From that point in time, the numbers have declined. In 1960, it was one in 44. In 2012, it was only one in 254.

This pipe find in Granby has a bore-hole that dates it to 1720-1750, which is the trader Thomas Brown period. These were the early days of Freemasonry. Benjamin Franklin was a founding member of the first Mason lodge in America in 1730. So, what does this all have to do with our pipe find? It all comes down to a maker mark on both sides of the pipe's spur. After much research, it all came together as I discovered this mark was not unique to the pipe maker himself, but it was an indication to "others in the know" that this came from a Freemason. More specifically, in our case, this "All Seeing Eye" mark almost certainly came from Odd Fellows.

"The Odd Fellows are one of the earliest and oldest fraternal societies, but the historical details of its foundations went strangely undocumented before the 18th century, creating some uncertainty about its name and origins. To understand what the "odd" in Odd fellows really means, we need to start with the order's purpose. For as long as records show, this has been an organization solely aimed towards charity and helping the less fortunate." The above image shows some of the evidence behind this secret maker's mark. It's probably unlikely that Thomas Brown was a member of the society. It may have just been a coincidence that the pipe fell into his hands. One thing for certain is, however, this pipe was made in England. The British did not do much in the way of pipe maker marks during these early Colonial days. This is the first pipe find in Granby that we absolutely know came from England. All the other pipes with maker marks came from Holland.

The one mystery that remains about this pipe is a metal artifact embedded in the artifact itself. It is as though a line was drawn down the stem toward the pipe bowl. Was it done before the pipe was fired (when the clay was soft)? Or, was it forcibly done after the pipe was hardened and maybe the pin-like instrument that made it was broken off and left in place to become a mystery for us. Was this done intentionally? Was it another message to be passed on from one Odd Fellow to another?

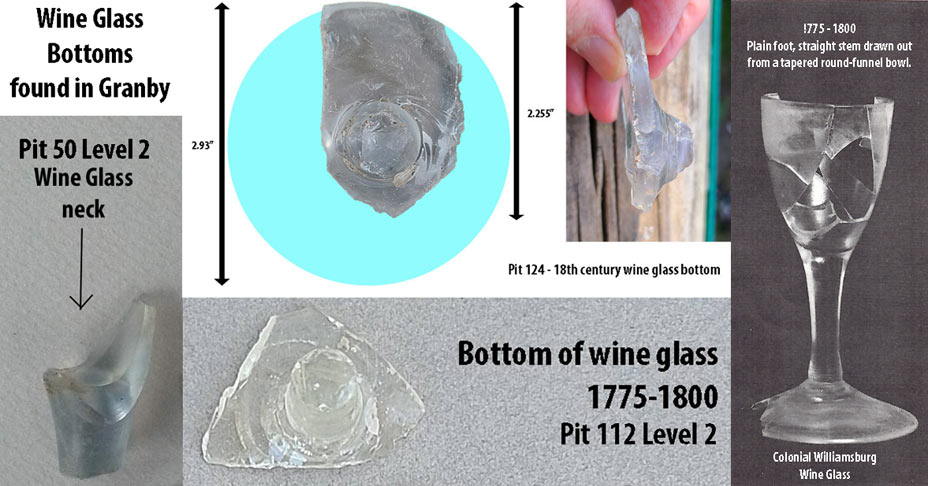

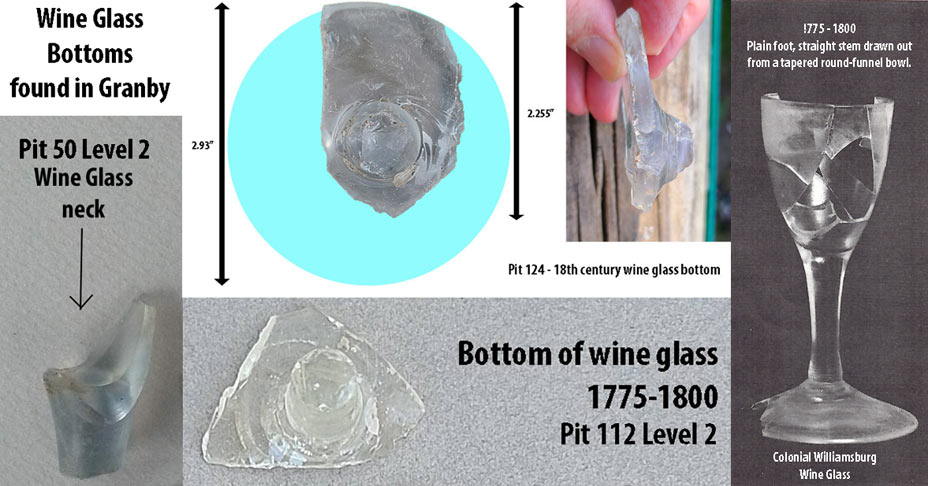

Number 41: Pits 50, 112, 124 - Wine glass bottoms

We have now found three wine glass pieces from the neck and foot of the wine glass. These match a wine glass style from 1775-1800 that has been found in Colonial Williamsburg. Digging up a full glass like this would be almost impossible because the bowl portion of the glass was made thinner during this time to save in taxes due to the 1745 Excise Act. This is yet another artifact type that supports the theory that Granbians were very wealthy people. Also supporting this are other finds like imported window glass, the many different expensive imported pottery types, and fancy glazed bricks.

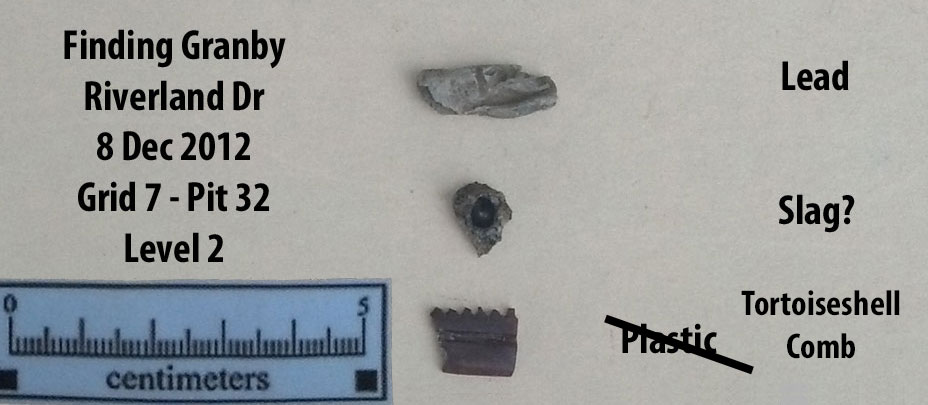

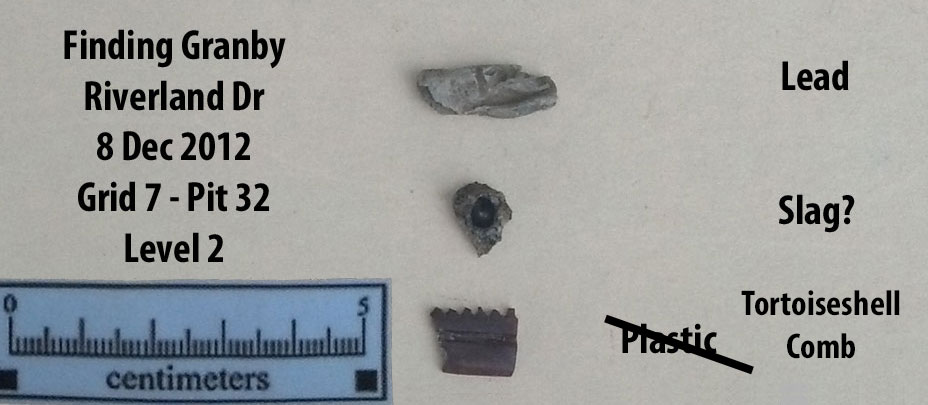

Number 42: Pit 32 - Granby Comb

Tortoiseshell combs were popular throughout the Victorian era as hair ornaments and grooming tools. The tortoiseshell was boiled in salt-water to create the comb shape, which rendered it malleable and able to be molded and carved. Once cooled, the combs hardened into their new forms. The term "Tortoiseshell" is misleading, as the shells of only certain tortoises and turtles, often the Hawksbill sea turtle, were used in the creation of these combs.

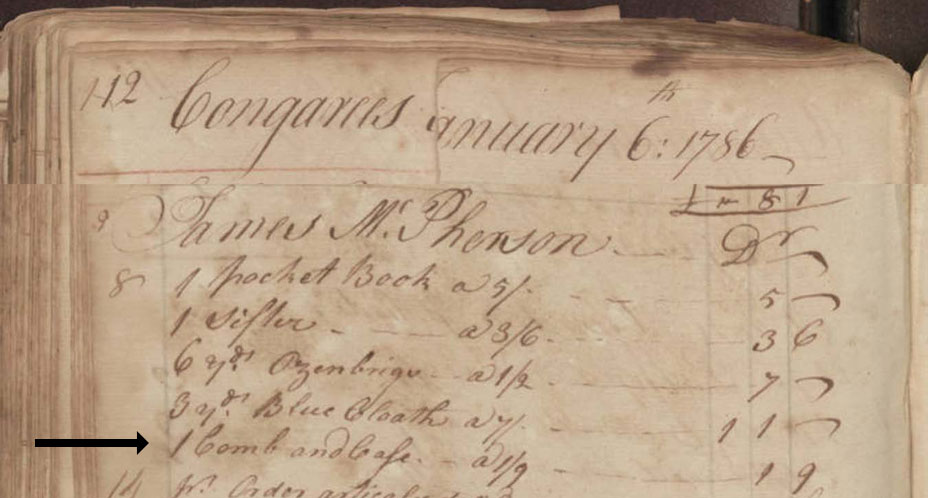

A "Fine tooth" comb was primarily used to remove lice and lice-eggs (nits) from the head. The Congarees Store account book for 1784-1786 shows 17 purchases that included combs. Three of those sales were specified as being "course" combs and seven of them were "fine" combs. One comb came in a case.

The optimal spacing for a fine-tooth comb (1.3mm between teeth) has not changed over the centuries. The tortoiseshell comb fragment we found in Granby Pit 32 has a tooth spacing of 1.4mm.

Number 43: Archival

- Congarees Store account book analysis

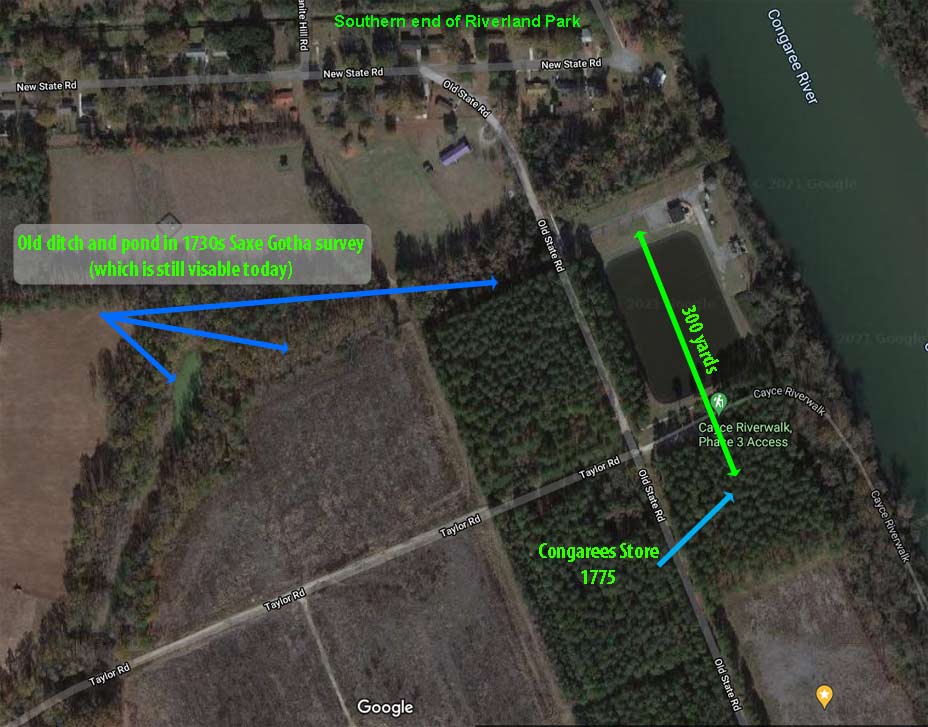

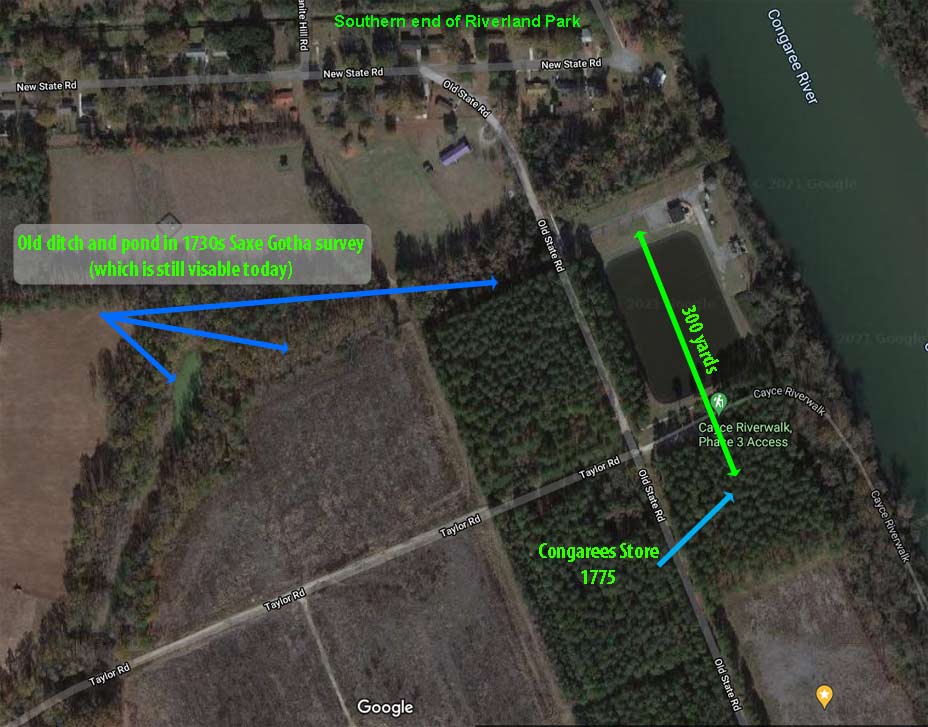

In the 1821 book: "Memoirs of the American Revolution, from its Commencement to the Year 1776, Inclusive, as Relating to the State of South Carolina" by John Drayton, we can see exactly where an important late 18th-century store stood. The Congarees Store was 1/2 a mile south of the south end of Granby (which was the Granby Cake Shop). John Drayton states that: "On Wednesday, the second day of August 1775, the Commissioners, William Henry Drayton, and William Tennent, left Charleston, in prosecution of the duties they had in charge; and proceeding by way of Monck's Corner, they arrived at the Congaree Store. The Congaree Store was situated about 300 yards below the large ditch, which crosses the public road (the Old State Road), just below Granby, and lay between the road and the Congaree River in the Dutch settlement of Saxegotha. Below is the location of the store.

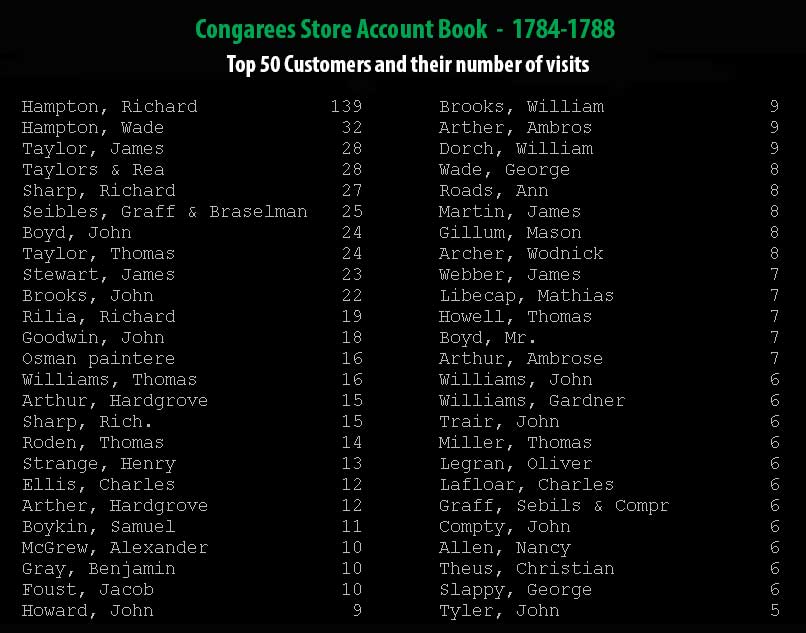

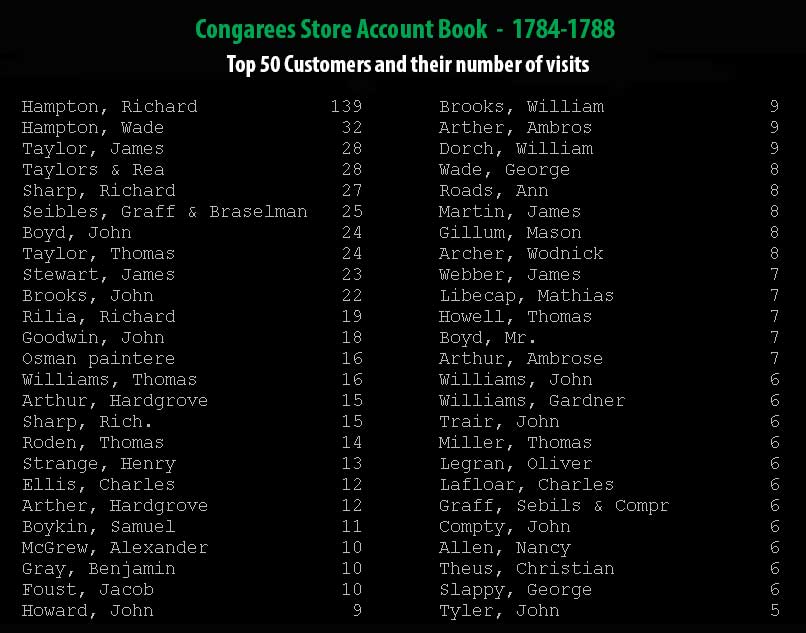

As part of her Master's thesis, Kathy Keenan painstakingly

transcribed the 1784-1788 Account book of the Congarees Store. This

book is held by the Cayce Museum and was recently digitized by USC.

Kathy's spreadsheet allows us to not only see who lived in Granby

during this time, but to also see what they were buying and the

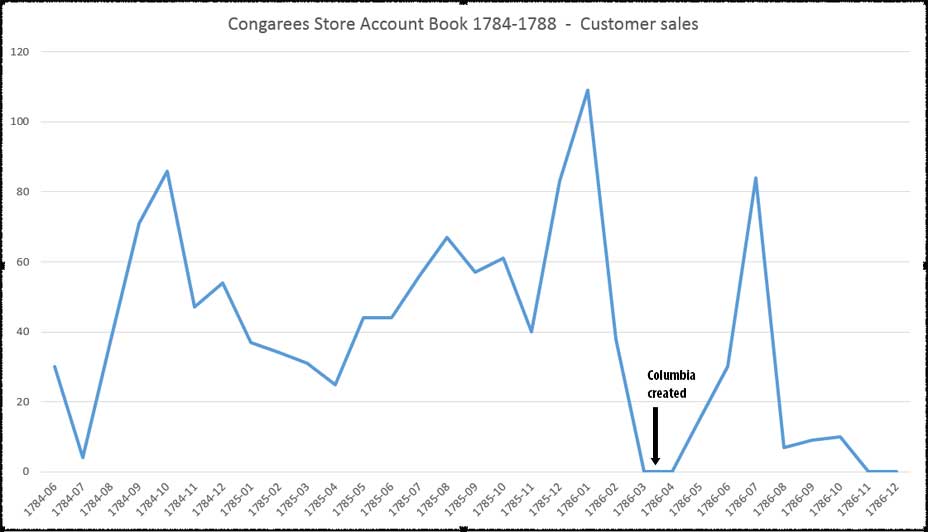

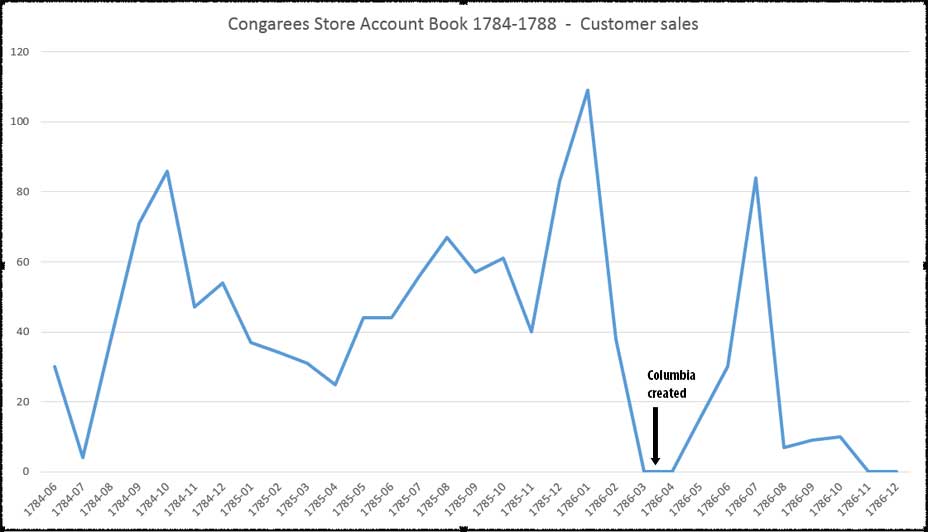

relative wealth of the people. The images here show just a few things

that can be taken from this data. The store is consistently busy during

this time period except for an abrupt and complete shutdown in the

months of March and April of 1786. This brings up the very important

question: What happened at this time?

By the end of February, 1786, Wade Hampton had made large land buys

around where the City of Columbia would be formed. He, apparently, had

inside information that the Capital of SC would not be placed in Granby

because of flooding and heath issues. On March 4th, 1786, Hampton's

friend Senator John Lewis Gervais introduced a bill to move the State

Capital from Charleston to a location "near Friday's Ferry". Gervais'

plans (no doubt involving the Hampton's and Taylor's) would soon target

the area of "Taylor's Hill", two miles north of Granby on the other

side of the Congaree River. As can be seen in the Congarees Store

account book, the Hampton's and Taylor's were the biggest customers of

the Granby store. The Hampton brothers had just purchased Friday's

Ferry in Granby in 1785. It seems very clear that these men saw a great

opportunity to make money on a land resale and were able to influence

Senator Gervais into selecting their desired site. On March 26th, 1786,

Gervais succeeded in having the City of Columbia created in the middle

of the Hampton and Taylor properties on the east side of the Congaree

River. This must have been a very anxious and exciting time in Granby.

On the last entry in the Congarees Store account book, before the

store's temporarily closing in March of 1786, the bottom of the page

has the word: "AMEN".

In April of 1786, the State of SC purchased over 1500 acres from the

Taylor and Hampton brothers for the main grid of the new Capital city.

On May 1st, 1786, the Charleston Morning Post reports that the area

around the new Columbia is buzzing with activity and that saw mills are

being built on every steam. The Congarees Store would re-open toward

the end of May. Business was slow in June and picked up very well in

July only to decline to nothing by the end of October.

Alert: Finding Granby research has recently uncovered evidence that

pin-points the location of the Congarees Store.

More top items to come....

As the excavation continued, it became apparent that this was not a tree or stump because there was no sign of roots. When we finally pulled it out, we began to realize this was a squared-off post with a diameter of about 22 inches and a length of about 21 inches. We would later discover that this post was exactly in line, perpendicular with the Congaree River, with a post hole (14 feet away) we found in pit 43 over seven years ago. The post position was also in line (90 degrees) with another hole feature we found in pit 113, about six feet away.

One last mystery about the post is that it has termites in it. Not very many of them, but several can be observed on the surface. How could a piece of wood like this have lasted for over 275 years with termites eating it? One explanation may be that the corner of the pit where the post was found is next to the corners of two pits (pit 67 and pit 69) that we dug in 2014. Maybe those excavations opened an easy (uncompacted) path for termites to travel. As well as moving our Finding Granby project into the preservation of iron objects (electrolysis), now we have to figure out how to try and preserve a possibly 275-year-old piece of wood.

You can learn more about these Civil War finds at this link.

"Instead of pinching off the tobacco flowers to make the leaves grow bigger, American Indians harvested the flowers (before they went to seed). The most prized smoking tobacco was that made from the flowers. Buffalo Bird Woman related to an anthropologist how the Indians made smoking tobacco, from planting the seed to final cure."

The careful excavation of the charcoal that was with these tobacco seeds could, through Radio Carbon Dating, give us a date for this Native American event. You can learn more about the ancient tobacco find at this link.

On October 7, 2021, the Cayce Historical Museum hosted a very informative talk by Historic Camden's Cary Briggs on brick-making. Did you know that sand is what gives strength to bricks? When a brick is over-fired, that sand will come to the surface as a glass (glaze.) I brought some samples of bricks we found in the Granby dig to have Briggs examine them. Most of our brick finds are "salmon-colored" small, fragile pieces that Briggs said were of low-quality production. He pointed out that a building like Fort Granby-Cayce House (today's Cayce Historical Museum is a replica of that) would have required about 60,000 bricks just for the two chimneys. That's about 5X what today's chimneys would use. That's 1.5 to 2 million pounds of bricks, which would be about five full truckloads of bricks today. Because of the weight involved, in 1780, these bricks had to have been produced on-site (in Granby.) Briggs also pointed out that there is no better place to find good clay than in the Midlands. He then explained to us the labor-intensive (but relatively simple) process of making bricks. The kiln itself was made out of the bricks that were to be fired. He brought a pre-fired brick (left to dry for about a week after molded) and a fired brick. I could not tell the difference (the feel or the appearance) between the two. But, the pre-fired bricks have more moisture in them and will not last long without being fired. So, for our Granby dig project, we now know where most of the brick artifacts came from. We do, however, also find a very strong brick that has a consistent grey color. These were probably made with a lump of completely different clay and by professionals. Our cheaper bricks were probably made, on-demand, by the Granby slaves who normally did other types of work. Historic Camden has a bunch of brick-making activities coming up. You can find out more at: Historic Camden Brick-making.

There are many personal purchases of bark in the Congaree Store for customers like John Boyd, Richard Relia, Benjamin Grubb, Gabriel Ragsdale, and David Renolds.

Turlington's Balsam of Life was a medicine patented by Robert Turlington in 1744. Turlington obtained his patent for the medicine's production from King George the second, making Turlington its exclusive manufacturer. With its 27 secret ingredients, Turlington claimed the medicine would successfully treat a wide variety of illnesses, including "kidney and bladder stones, cholic, and inward weakness."

The most distinguishing feature was the rainbow color of the glass artifacts. The glass of the old Turlington bottles tends to have a chemical reaction when left in the soil over many years, giving the glass a rainbow color. The reaction is caused by the interaction of the patina and the chemicals used in creating opalescent glass. This unique and rare effect leaves little doubt that the glass pieces of Granby pit 142 are from a Turlington bottle.

The patent that Robert Turlington had enabled him to specify who sold it. It made its way to the Congaree store through Charleston.

The store's biggest customers, by far, were Richard and Wade Hampton, and they also purchased the most bottles of Turlington. We don't know what their specific ailments were, but they made multiple purchases over a period of six months in 1785. The purchases stopped after that, so we can guess that the Hamptons were not impressed.

Below is a display that shows the different nails that have been found in the Granby dig.

In the 18th century, broad glass and crown glass were the two primary types of window glass. It isn't easy to distinguish between the two. About 3700 pieces of window glass have been found in the Granby dig. The thickness of our glass varies between 0.4mm and 0.9mm, with the average being .7mm. The variation in glass thickness has to do with the way the glass was made. The smallest piece of glass shown in the display is the thickest (0.9mm), and it has the characteristics of being part of the rim. This rim discovery and the wide variation of glass thickness almost certainly means that our Granby glass was the more expensive crown glass.

"To make crown glass, a bubble was blown and then cut at one end; the resulting cone was spun on pontil rod, causing the glass to spread out into a circular sheet. Because it cooled while still suspended in air, crown glass was clearer and more brilliant than broad glass; consequently, it was the more desirable and the more expensive type of glass. The circular sheets could vary in diameter from 2 to 5 feet, with 3 or 4 feet being the most common size in the eighteenth century. The panes that could be cut from the disc were limited in size by the thickened rim and the thick "bull's eye" in the center, where the glass was broken from the pontil rod. The bull's eyes were sometimes discarded, but they were also used in more poorly constructed houses or where good visibility was not required. It is not always possible to distinguish between the two types of glass from excavated examples. Sometimes, crown glass is found with part of the rim or bull's eye attached, which makes identification certain. Such glass found in Williamsburg is generally blue-green in color, only slightly decayed, and occasionally has curved lines of bubbles or stress marks. Identical glass, when found without the rim or bull's eye, also may be assumed to be crown glass. In contrast, much of the broad glass found is of a pale grayish-green color."

"The indigo plant had been first brought to North America into South Carolina in 1742 by Elizabeth Lucas Pinckney, and had become one of the main home industries of this area. Millions of pounds were also shipped to the dye plants in Europe. Sometimes the plant grew wild, but as a chief source of income it was cultivated. The ground was plowed near the end of the year, and some mulching done. In the following spring the seeds were sown. The plants were cut two times each year, once in the early or midsummer, and the second time about two months later. The dark blue dye was used in calico printing and dyeing, also for other materials."

Chambers later notes:

"The last record found of Granby as one of the LEADING TOWNS of South Carolina was in 1815. Rumors of mosquitoes and a low, sandy place were circulated when the talk of changing the Capital from Charles Town to some central place was in progress (in 1786). This had its effect on the popularity of the town. Many of the Granby people who grew indigo plants were building summer homes in other places, because of the many mosquitoes. The water used in making the dye for home use became stagnant and thus bred millions of mosquitoes." Check out the many cool items found in level 3 of pit 43 at this link.

Side note: The discovery of Fort Congaree II (shown in the above land plat overlay) also gives more proof to Brown's property location. The adjacent Fort Congaree II property and Brown's property shared the same pond. Elevation mapping of today shows the pond is still there today although it only fills with water (to the dismay of Riverland Park residents) when the river is high.

See more about the Granby land plats at this link. Learn more about the people who lived in Granby at this link. Find even more about the people who lived in Granby by clicking on places in Sarah Friday's 1810 drawing of Granby at this link.

This pipe find in Granby has a bore-hole that dates it to 1720-1750, which is the trader Thomas Brown period. These were the early days of Freemasonry. Benjamin Franklin was a founding member of the first Mason lodge in America in 1730. So, what does this all have to do with our pipe find? It all comes down to a maker mark on both sides of the pipe's spur. After much research, it all came together as I discovered this mark was not unique to the pipe maker himself, but it was an indication to "others in the know" that this came from a Freemason. More specifically, in our case, this "All Seeing Eye" mark almost certainly came from Odd Fellows.